Superheroes have been dominating big and small screens for a while. But there’s a subtle change happening. Kids are starting to expect to develop superpowers themselves. They think that a decade from now they will be able to enhance both mind and body, augmenting human capabilities. Will they carry heavy weights effortlessly? Be able to see in the dark without cumbersome headsets?

These expectations may sound like a movie script. But we’re already making the first strides towards this 'augmented society'. Trade fairs are boasting AR goggles that show technicians where a particular screw should go. Your own phone gives you information about your fitness in real time or tells you about the latest fad.

Augmentation can be defined as the extension of rehabilitation. There, technological aids such as glasses, cochlear implants or prosthetics are designed to restore a lost or impaired function. But add those to completely healthy individuals and such technology can augment. Night goggles, exoskeletons and brain-computer interfaces make up the picture.

The augmenting technology will help in all stages of life: children in a learning environment, professionals at work, ambitious senior citizens. There are many possibilities.

Say what?

Here’s a scenario. You’re talking to someone in a noisy setting, at a bar, at a party. Even though your hearing is fine, the situation makes it extremely difficult to understand your companion. Imagine you could just put on glasses or earbuds that offer the same sound directionality as a hearing aid.

Or another example: many children with attention deficit struggle in school. In the best case, they get special education services or classroom accommodations. However, with extra visual and audio guidance that blocks off excess stimuli, otherwise-enabled children can cope with a standard school environment. And when class is over and playtime begins, they can just take the aids off.

Augmentation doesn’t end there. Your phone might feel like part of your body but it’s not put in through surgery. Technology will become more intertwined with the body in the form of implants. But it will also seamlessly integrate in the environment – you might have sensors in a chair, for example.

Are we moving towards a ‘brave new world’? Chip implants may sound scary. But they form part of a natural evolution that wearables once underwent. Hearing aids or glasses no longer carry a stigma. They are accessories and even considered fashion items. Likewise, implants will evolve into a commodity.

If that sounds unlikely, then consider the alternatives we currently use. Drugs often show unwanted effects because they affect multiple biological processes at the same time. Someone on long-term medication may want to try an implant that sends very precise electrical or optical pulses instead.

Getting an implant is obviously more invasive than picking up a pair of glasses. Generally, implants will be linked to medical conditions. The extent to which a particular device becomes common will depend on the technology’s functionality and how far it’s integrated in your body, and daily life(style). Carrying around the equivalent of a dog’s nose in a gadget like your phone or a wearable like a necklace can be handy to sniff out COVID-19 or food allergens. In those cases, it's usually enough that your phone pings whenever you’re in the vicinity of whatever you want to be protected from. There's no immediate reason to implant this extra sense into your body. However, a deadly peanut allergy may justify a more permanent solution.

All in the mind

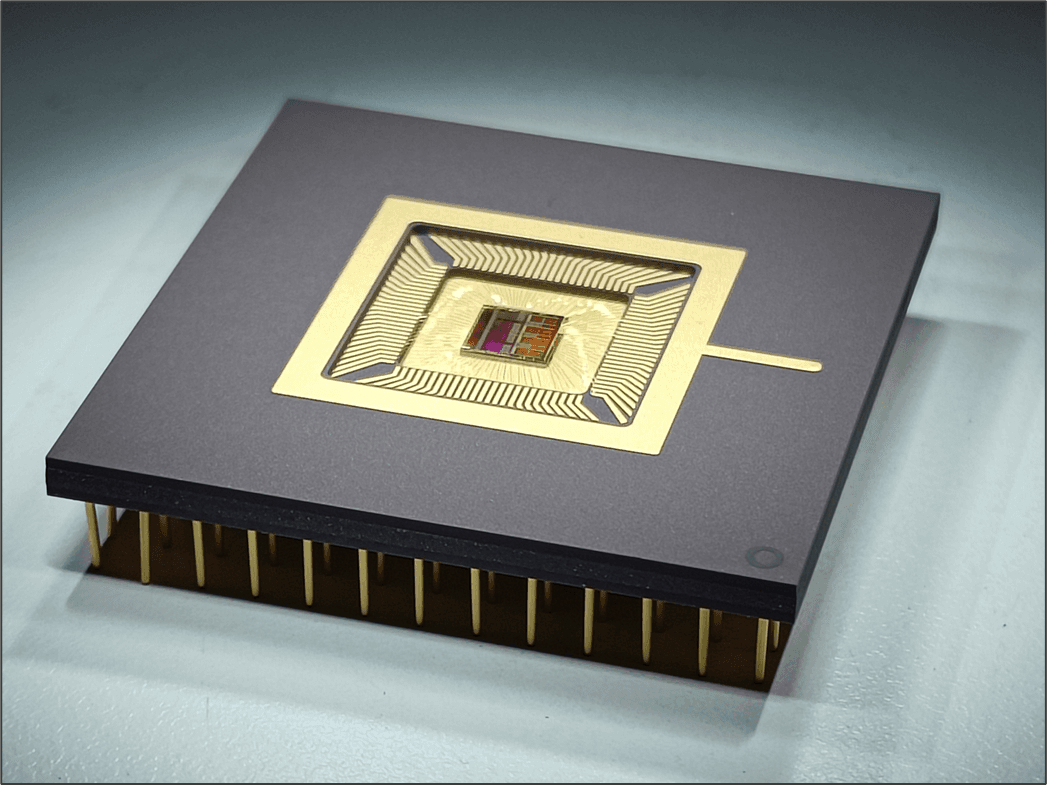

Brain implants take us one step further and allow us to tap straight into the body’s 'operating system'. We've already started interfacing with the brain using neural probes to mitigate symptoms of epilepsy, Parkinson’s Disease or depression. Most applications will remain based on medical necessity rather than a mindreading tool. While it is true that companies like Neuralink have been targeting the brain from the get-go, brain implants may not be the first choice for augmented humans.

In fact, we skipped a few steps. An indispensable wearable device may be implanted under the skin as a first approach, or in the belly if needed. For example, for patients suffering from urine loss, a small stimulation device tucked away in the pelvic area constitutes a more elegant and comfortable solution than wearing incontinence pads.

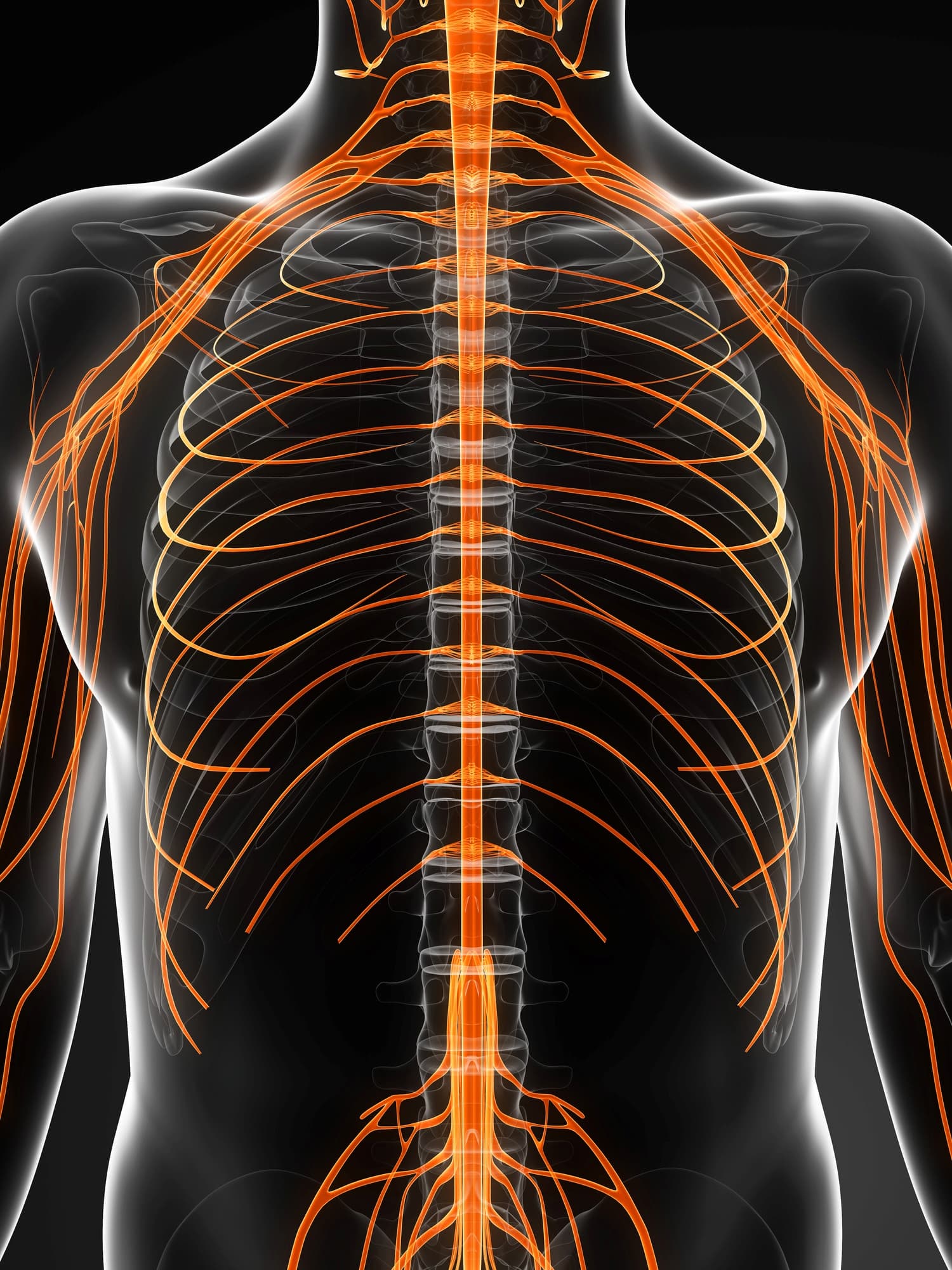

Next, you can think about other implants that influence the nerves of the peripheral nervous system. Or the information highways that connect the spinal cord and brain to organs and limbs. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve, the superhighway that originates in the brain, is rumored to be a miracle therapy for treatment-resistant depression, an ever-growing problem.

Despite all these options, some therapies will only be effective in the brain, but would you walk around with a chip in your head?

Accept or augment our human limitations?

Just as with wearables, no one turns their head anymore for medical necessities, for a hearing aid, for a pulse monitor. Even in an educational and professional setting, smart goggles, phones, wristbands and the like are commonplace. Gaming is the next target.

The question is whether implants will follow a similar evolution. Health? Plausible. Education and profession? Potentially. Of course, I would like to give my dyslectic child all opportunities with an implant that translates in real time. On the other hand, dyslexia is a personal trait, do we want to change that? As a society we need to make a choice: do we want to accept human limitations, associated with learning but for example also with aging? The final application realms, gaming and even intelligence augmentation, may seem farfetched but only the future can tell.

If the idea of a chip in your body makes you cringe, consider all the pharmaceuticals you take without question. The art installation ‘Cradle to Grave’ in the British museum confronts us visually with our pill-popping behavior. It displays a 13-m long fabric interwoven with 14,000 pills, the estimated average prescribed to a British person in a lifetime.

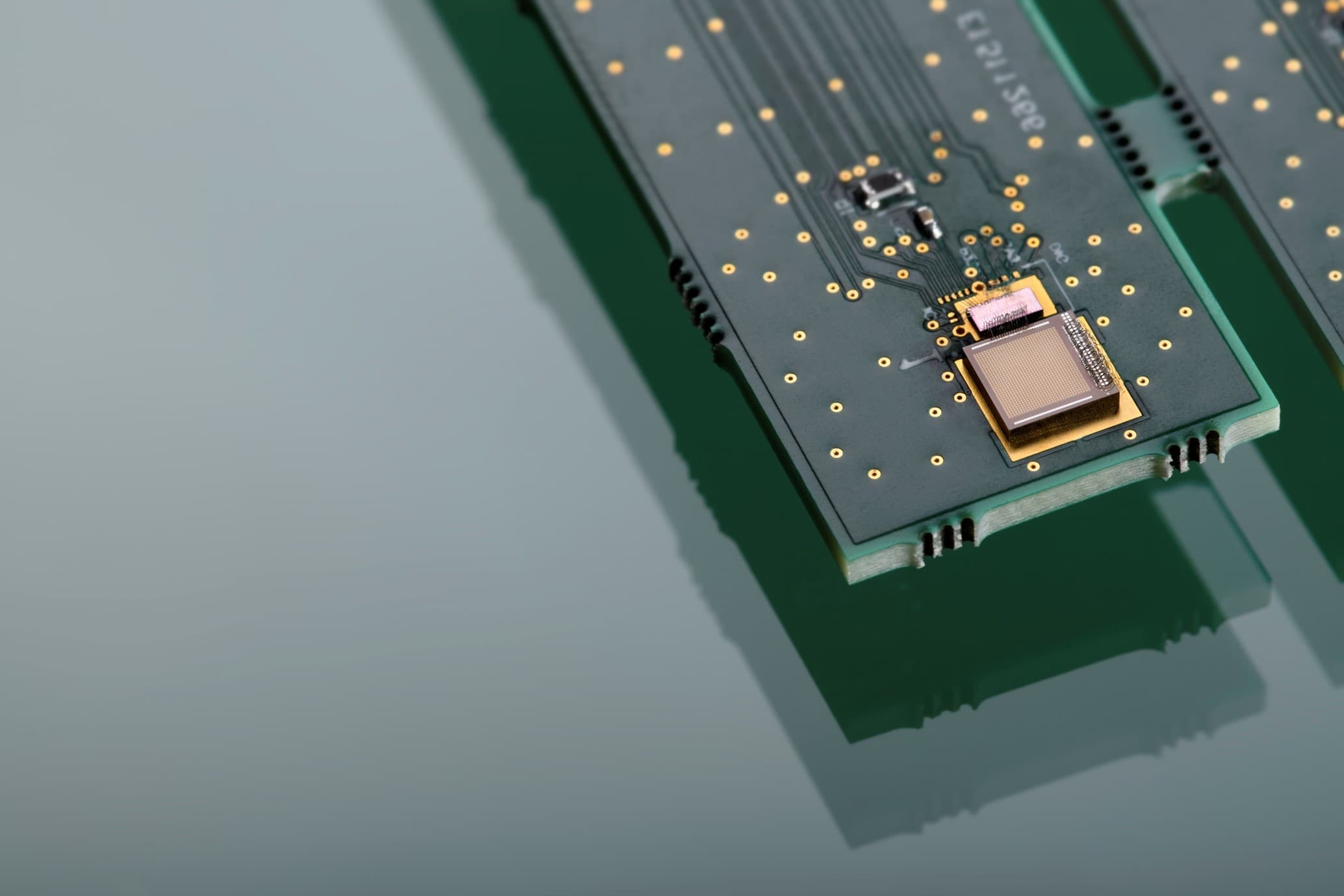

More numbers: around 65% of American children and teens with ADHD are prescribed stimulant medication such as Ritalin or Adderall. We often forget that these drugs are related to amphetamines. They affect the brain and have (long-term) side effects. Then why not consider electroceuticals, small implants that mitigate symptoms of various disorders by sending out small electrical pulses?

One compelling argument in favor of bioelectronic medicine is that the stimuli can be stopped at a flick of a switch literally, while drug effects linger in the body for a longer time.

The limits on implants are going to be set by ethical arguments rather than scientific capacity. Let’s take this example: should you implant a tracking chip in your children? There are solid, rational reasons why you should. Safety, for one. But would you actually do it, is it a bridge too far?

Another important element is security. Remember when Dick Cheney’s pacemaker was modified to prevent hacking? Even for lifesaving technologies proper ethical counseling and legal framing are a must.

The real boundaries will be drawn in the ethical debate. Ethics should not be preached from an academic Ivory Tower. Rather, overarching or independent institutions should guide policy makers and researchers in the augmented society on the do’s and don’ts and help build the ethical framework on societal aspects of augmentation technology. An international organization, the Council of Europe, has recently launched a strategic action plan tackling issues raised by the applications of neurotechnologies.

Another example, Rathenau Institute founded by the Dutch government, operates as an independent institution to reflect on questions related to the impact of technology on our lives.

Chile is already one step further. Last year, the country pioneered with a bill to amend their constitution to protect personal brain data. Several countries are now exploring how to address these issues surrounding (brain) implants. The task is daunting as ethicists will not only need to scrutinize blooming technology but also potential future applications.

From health care to well care

Technology will not necessarily be the limiting factor. Even when we’re talking about mindreading, flying or becoming invisible. With the right support, vision and audacity these transformative technologies – that go beyond augmentation – become possible. When do we enter the grey zone? Ethics will advise us.

The technology optimists show what is possible with augmentation. Technology has always had the potential to transform society and improve our daily and professional lives. So does augmentation technology. It goes hand in hand with an evolution from health care to ‘well care’. There, it’s not just about solving an impairment anymore. It’s about technology that supports you and improves your overall quality of life.

This article was previously published in World Economic Forum.

Dr. Kathleen Philips is VP R&D and General Manager of imec Netherlands within Holst Center. She has been promoted in electrical engineering, is author and co-author of more than 60 papers and holds several patents. Philips joined imec in 2007 where she was chief scientist and led leading research programs in the field of Internet of Things. Before imec she was a scientist at Philips Research for over 12 years.

Published on:

18 August 2022