Intro

The start-up Fluves, which is part of the imec.istart acceleration program, is specialized in continuously measuring and monitoring underwater depth. A niche market with potential. Their technique cannot only be used to monitor the movement of contaminated sediment in rivers, but can also be used to make sure that the submarine power cables that are used to transport electricity from offshore wind farms to the shore remain safely hidden underneath the ocean floor.

The weakness of submarine electricity cables

The energy generated by wind turbines at sea is transported to the shore through a thick power cable. In an ideal situation, this cable is buried about 1 meter underneath the ocean floor, but due to the natural movement of sandbanks in combination with the effects of fishing (fishnets) it’s possible that the cables become exposed after a while.

It’s very important to avoid this, because cables that are not at the right burial depth can easily be damaged, e.g. by the anchor of a fishing boat.

If that happens, the whole wind farm has to be switched off until the cable is repaired. This could cost up to 10 million euros.

To solve this problem, Fluves teamed up with Parkwind (a consortium of the Colruyt Group, PMV and Korys). Parkwind develops, finances, builds and operates wind farms in the North Sea. Together they developed a cost-efficient solution – based on fiber optic technology – to continuously monitor the burial depth status of submarine power cables. In 2016 they managed to get a grant from Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship (VLAIO) to further develop this concept.

Glass fibers can determine how deep they are buried

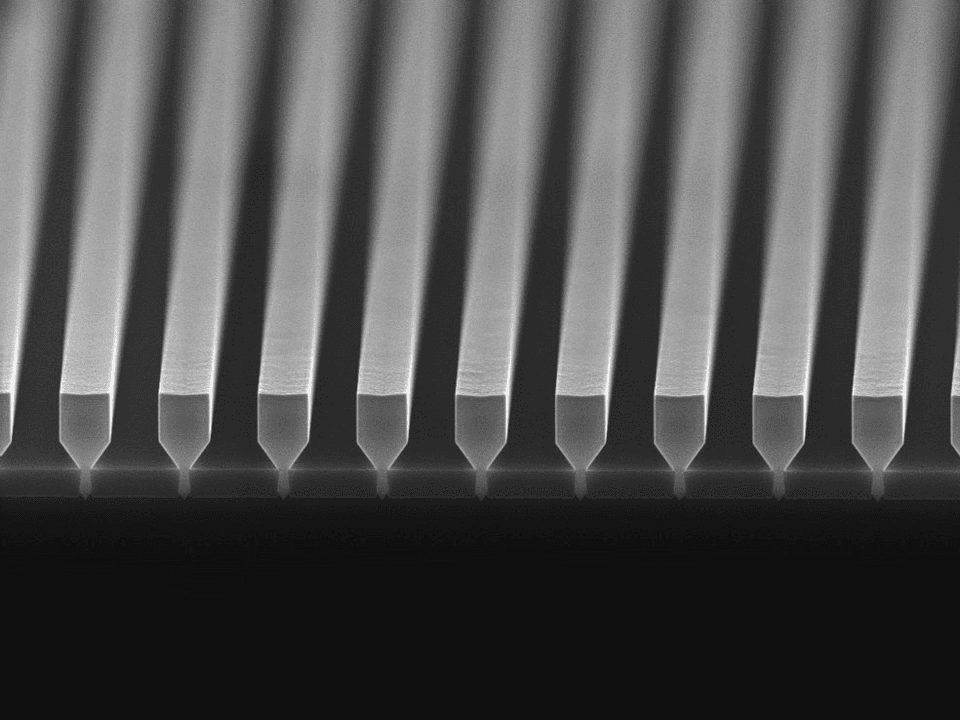

Optical fibers are used in different ways in a variety of sectors. In the oil and gas industry, for example, they are used to measure the pressure in boreholes and to map oil fields. But the most well-known application field of optical fibers is undoubtedly telecommunication. Optical fibers (like glass fibers) can be used to transmit information fast and across long distances.

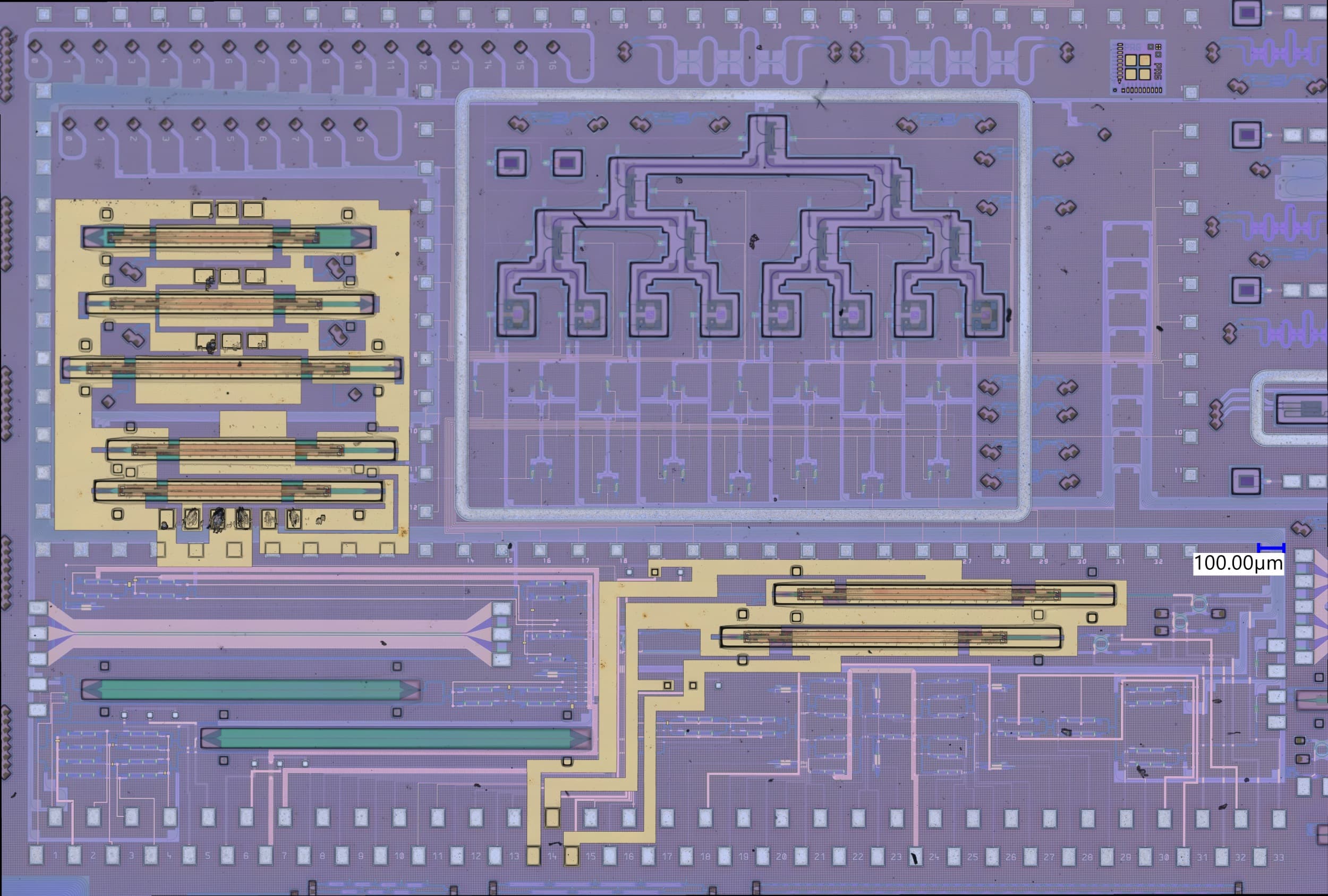

For this reason, optical fibers are often integrated into submarine power cables. Offshore wind farms use glass fibers to transmit data about the turbines’ functioning. A submarine power cable contains up to 100 optical fibers. Generally, only about 50 of those are in use.

Fluves uses one of the available fiber optic cables to measure the temperature of the power cable at different points (every 10 meters) and at regular intervals (every 20 minutes).

This information is the basic parameter that Fluves uses as a starting point. With their advanced algorithms, they then calculate how much soil or sand is on top of the cable. The alternative to the Fluves technology is to check burial depth with inspection boats or unmanned submarines, but because this is rather expensive, the check-ups can’t take place regularly. Thus, with the old method, wind turbine operators do no not get a good overview of how the situation is evolving.

Another strength of the Fluves technology is that the software can even predict how the situation will change, so preventative measures can be taken. Moreover, the Fluves software presents the data in a clear and user-friendly way, allowing wind turbine managers to identify problematic areas in a simple and efficient way.

Stronger together: finding the right partners at the right time

The Fluves story begins in 2014 when Thomas Van Hoestenberghe decided to start his own company. At that time, he was working in the water and dredging industry. In this position, he had come into contact with fiber optic technology multiple times. He became convinced that there were unexplored opportunities for this technology in his field. This idea was the beginning of Fluves. The original focus of the company was not on submarine power cables though; instead the start-up focused on projects in lakes and rivers.

They installed optical fibers at the bottom of rivers and lakes and measured the tension and temperature of the cables. With this data, Fluves can determine how much sediment is located on top of the cables. The technique can be used in several situations, e.g. to determine whether contaminated sediment is polluting the water or to check the efficiency of sediment traps.

Thomas Van Hoestenberghe: “In the beginning, it was really bootstrapping. I tried to do most of the work myself and with a limited budget. I still remember being on a surfboard in a river to check the measurements of one of our first projects.”

A year later, Roel Vanthillo, an old acquaintance from Vlerick Business School, decided to join the company. He had experience and contacts in the wind energy sector. This prompted Roel Vanthillo and Thomas Van Hoestenberghe to try and combine the Fluves’ software and algorithms with the existing glass fiber technology in submarine power cables.

Together they submitted an imec.istart application and in November 2016 they joined the program. Thomas Van Hoestenberghe is convinced of the added value of imec’s business accelerator program: “When you start a new company, you can definitely use advice, but it needs to be targeted advice. The coaching sessions and workshops that were offered as part of the imec.istart program were really valuable to us in this context.”

The financial support of 50,000 euros also allowed Thomas to focus on Fluves fulltime and – simply by being selected – they were also approached by an interested investor. Thomas Van Hoestenberghe:

“Before we joined imec.istart, we had to swim really hard to keep our head above water. Thanks to imec’s support, it’s like we suddenly ended up in a life boat, allowing us to move forward much faster.”

About the same time, Fluves also entered a partnership with Parkwind. Together they landed a VLAIO (Flanders Innovation and Entrepreneurship) research project to further develop their technology to monitor submarine power cables. Thomas Van Hoestenberghe: “Working together with Parkwind was an important step for us. They have a lot of knowledge and a large network in the sector. They also have the budget and the possibility to invest in new projects.”

Although he strongly believes in the importance of strategic partnerships, Thomas Van Hoestenberghe does add that it’s important – as a start-up – to do enough preparatory work before entering such a partnership. “The bootstrapping that we did in the beginning, with our own money and in our own time, provided us with a firm foundation to rely on during negotiations. You have to make sure that you already have a well-developed idea, a ‘proof of concept’, before you decide to team up with a large industry partner. You have to be able to prove the added value you bring to the table.”

The future: beyond wind energy

Nobody knows what the future may bring, but Fluves clearly has big plans. Together with Parkwind they are planning to bring to market their jointly developed technology for submarine power cables. The aim is to go beyond the wind energy sector. Their technology could also be used for wave or tidal energy, submarine data cables (e.g. between America and Europe) and other offshore electricity networks. All these cables generally contain optical fibers to transmit data, so the required hardware components are already there. They aim to enter both the national and international market.

In the meantime, Fluves wants to continue its onshore projects (in rivers and lakes) as well. In these projects, they also take care of the hardware side of things (selecting and installing the optical fibers). At the moment, they are already working on their first international project in the United States.

Thomas Van Hoestenberghe, CEO and co-founder of Fluves, worked as a manager in several engineering firms, focusing on water-related projects in Belgium and abroad. In this way, he came into contact with different kinds of technology that could be used to measure the dynamics of soil and water in rivers, harbors and seas. Thomas is a bio-engineer, but also holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Law and obtained an MBA from Vlerick Business School.

Roel Vanthillo is an industrial engineer in electro-mechanics. He started his career with the dredger Deme, where he gained experience with offshore wind farm projects during the construction of the C-Power site (2007-2008). In 2009 he started working at Cofely Fabricom, where he collaborated on the design, construction and initial operation of high voltage stations and offshore wind farms. He then worked at the automation company Egemin until he joined Fluves in 2015.

Published on:

27 September 2017