Plenty of exercise, healthy eating, not smoking and keeping your stress under control. We all know how things ought to be for healthy living. But it’s not because we know what’s right for us that we actually manage to apply it, too. Yet 80% of chronic diseases are linked to our behavior, while treating those diseases gobbles up 50% of the healthcare budget. So it’s high time for some good intentions or, even better, for a system that helps us to put our good intentions for a long and healthy life into effect.

Imec is building just such a system, based on sensors and the analysis of smartphone data. Chris Van Hoof, director Wearable Healthcare at imec, talks to us about this major research program, which includes sensor technology, data science, extensive trials, developing business models and, most importantly, finding the right partners. Various hospitals are already involved in the program. And because solid foundations have been laid for the program, Chris Van Hoof is now looking for interested companies seeking ways of changing healthcare forever.

How does imec intend to tackle chronic diseases?

We all know that a healthy lifestyle is important. It saves us from obesity, cardiac and vascular diseases, burn-out and depression, as well as certain forms of cancer. Yet it can be so enjoyable to eat a pizza or fries from time to time, or (even) to smoke a cigarette – and many people think that stress is part and parcel of work anyway. Which is why imec is developing a system that will encourage us to live more healthily and help doctors in treating patients with depression, eating disorders and so on.

Van Hoof: “It all begins with collecting data. We take physiological data readings using sensors that you wear on the body (such as in a watch, incorporated into a T-shirt, etc.). This may involve all sorts of cardiopulmonary parameters and physiological information, including heart rate, ECG, skin temperature, skin conductance and so forth. We then gather contextual data using your smartphone: your location, the appointments in your diary, your activity on social media, ambient sounds, e-mail habits, etc. NB: just by way of reassurance, this data is made anonymous for privacy and security reasons.”

“We then apply smart algorithms to all this data, which gives us an insight into your behavior, habits and ‘moments of weakness’. For example, you may always go for a smoke at around midday and four in the afternoon, or your stress levels may rise when you have a meeting with a specific person, or you may like to snack on something sweet when you get home from work. In this first phase, the system gets to know you, although feedback from the person is often still required. However, this feedback needs to be very user-friendly. It doesn’t make sense, for instance, to ask people who want to lose weight to fill in an eating diary, because no one will keep it up. But if the system succeeds in deducing as much as it can from contextual information – and if the questions have simple Yes/No answers – then most people will find that acceptable. In fact, the better the algorithm gets to know you, the more focused the questions will be that you have to answer.”

Collecting and interpreting physiological and contextual data enables you to pick up on a person’s habits. This is the first step in the process of changing behavior.

Once we have gathered all of the data we need and gained specific insights from it, what is the next step? Van Hoof: “People often know when they are having their moments of weakness, but this is not enough to make them do anything about it. What they need is someone to support them during these vulnerable times. Think about the image of an angel and a devil perched on your shoulder when you want to quit smoking, eat less candy, etc. We want to put an additional angel in your smartphone to tilt the balance in your favor. So, imagine that you want to improve your fitness. The algorithms have already learnt what your current fitness levels are, whether you are a morning or an evening person and when you have time in your busy schedule. Based on this information, they can suggest that you do certain exercises at certain times. Or maybe you want to stop smoking: the algorithm has learnt where it is you go to have a cigarette and will send you a message as soon as it notices you are heading in that direction. Or perhaps the algorithm has learnt that you always smoke after visiting your mother-in-law. What it does is send you a message immediately after this ‘risk time’ to convince you not to light a cigarette. This differs from the current applications, which send you general tips and advice at standard times. The key to success is to get to know the person, the way they spend their time and what their habits are, so that the right feedback can be given at the right time. We supply the technology; the behavioral therapists provide their insights into how best to help and guide a change in behavior.”

Five cases

A number of actual cases will be dealt with in the research program into technology for changing people’s behavior. Van Hoof: “We will develop technology and algorithms for stress management, quitting smoking, changing eating and drinking habits (e.g. for losing weight), as well as for improving fitness. We know that there are already lots of fitness apps and activity trackers, but we believe that we can develop technology and algorithms that will make these products even better. So that they provide personal feedback, at the right times. The companies that make these types of apps are more than welcome to work with us on finding solutions that make people genuinely healthier as long as they live.”

“We start with ‘extreme’ cases so that we can learn things that can be used later in less extreme cases. Example: for the stress management exercise, we work with patients who are being treated by a therapist and who are struggling with burn-out or depression; for eating habits, we work with anorexia patients. If we can detect signals in these patients that are typical for their ‘disease’, at a later stage we will also be able to identify disorders that are less obvious and so take preventative action. If, for example, we are able to detect chronic stress at an early stage – before it develops into burn-out or depression – we can protect the patient, doctor and healthcare budget from more significant problems.”

Current results

The idea we are talking about here is not new for imec. We have written about it previously in imec magazine (see article headed ‘A personal coach for everyone’, September 2015). But a lot has happened since then. Van Hoof: “Last year, imec merged with the iMinds research institute. Their researchers have brought their knowledge about data science and security with them, which makes our program even stronger and more complete. We have also been running a large-scale trial (1000 people) on stress for the past 18 months. We measure stress parameters in their daily lives and analyze this data looking for a way to detect stress accurately and possibly to predict it. This enables us to subdivide people into various categories in relation to their ability to withstand stress. For this stress trial and also for projects on eating behavior among anorexia patients, we work closely with psychologists and therapists. Setting up this form of collaboration provides the important foundation we needed before we were able to roll out a large-scale research program for industrial partners.”

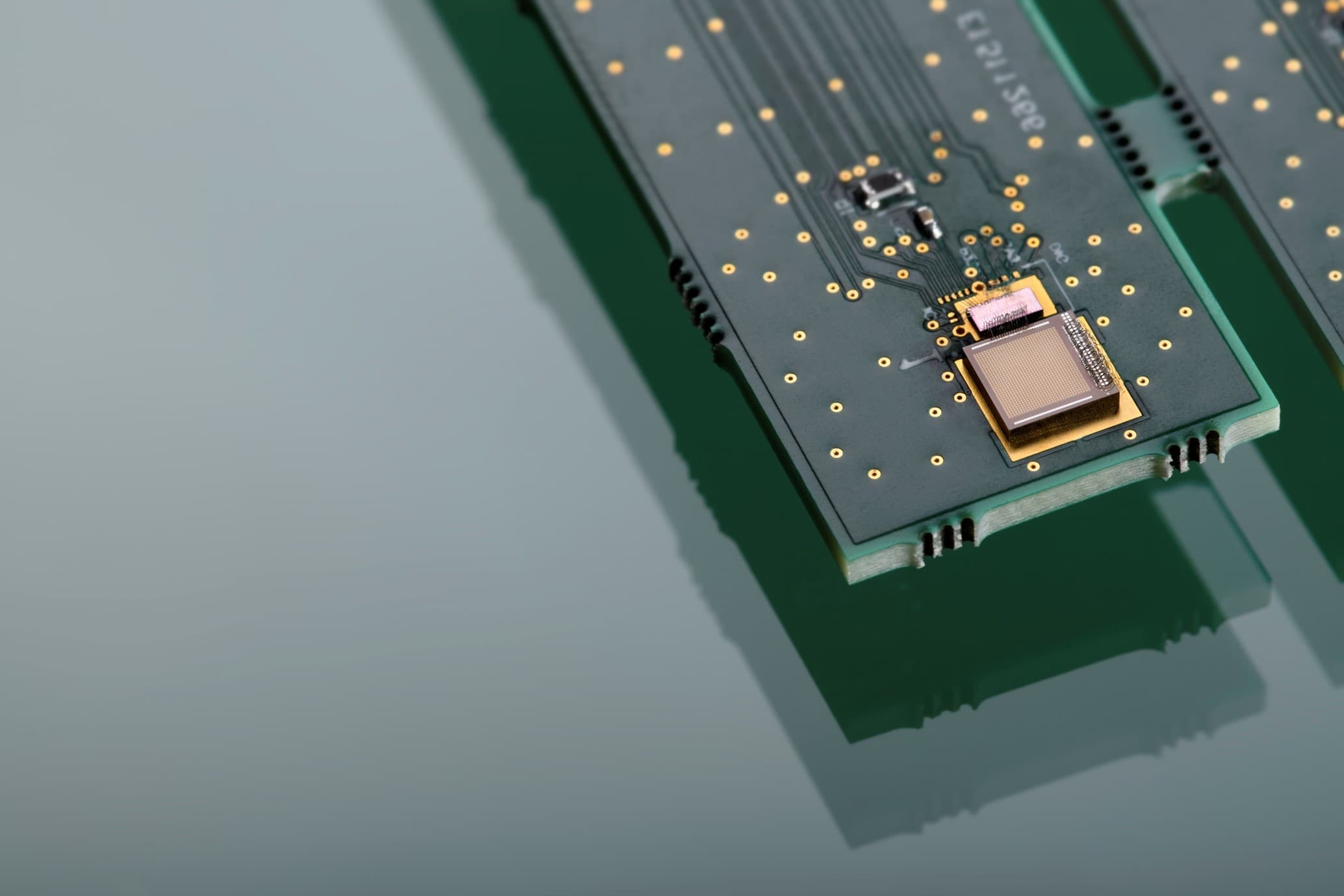

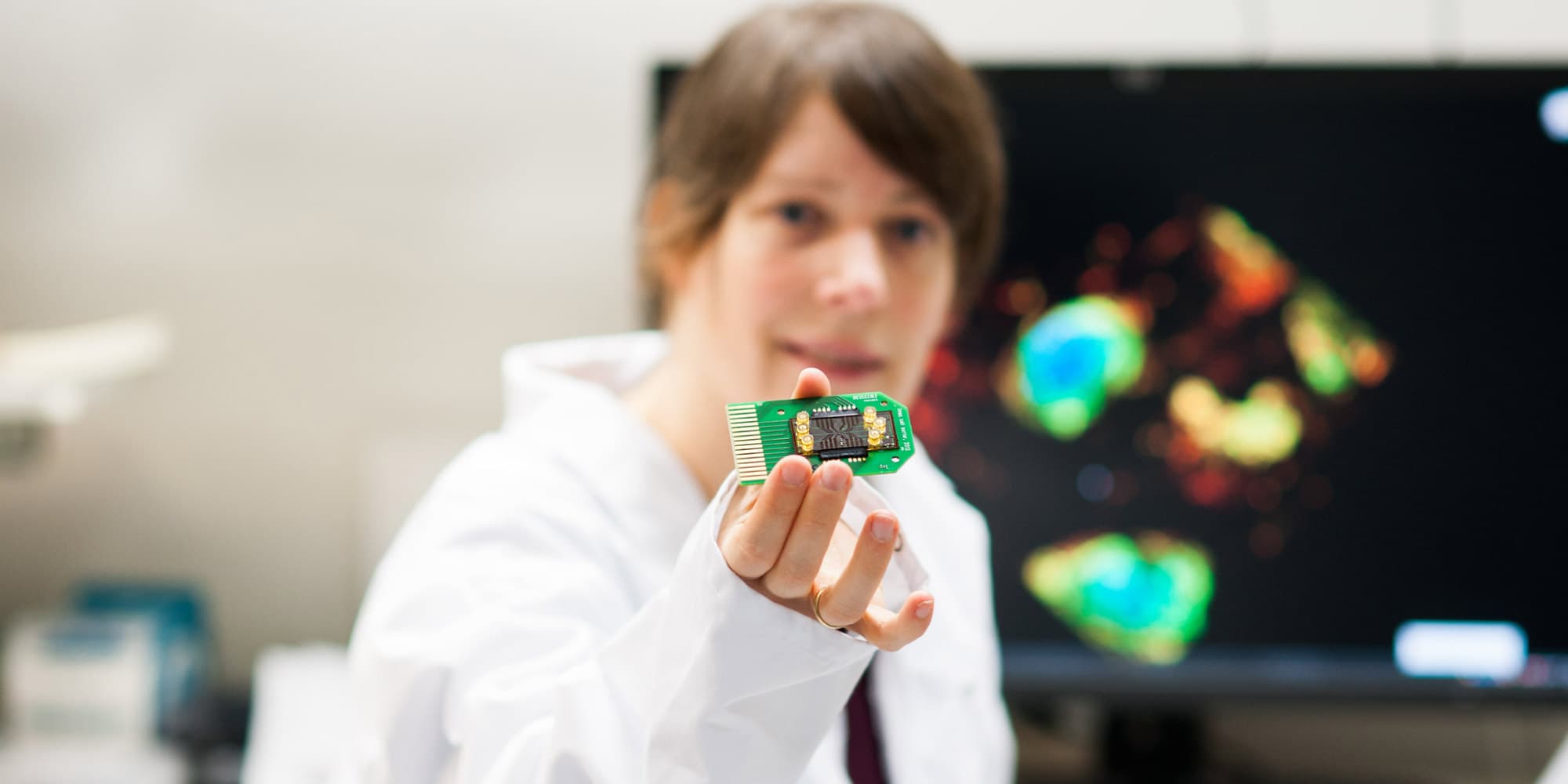

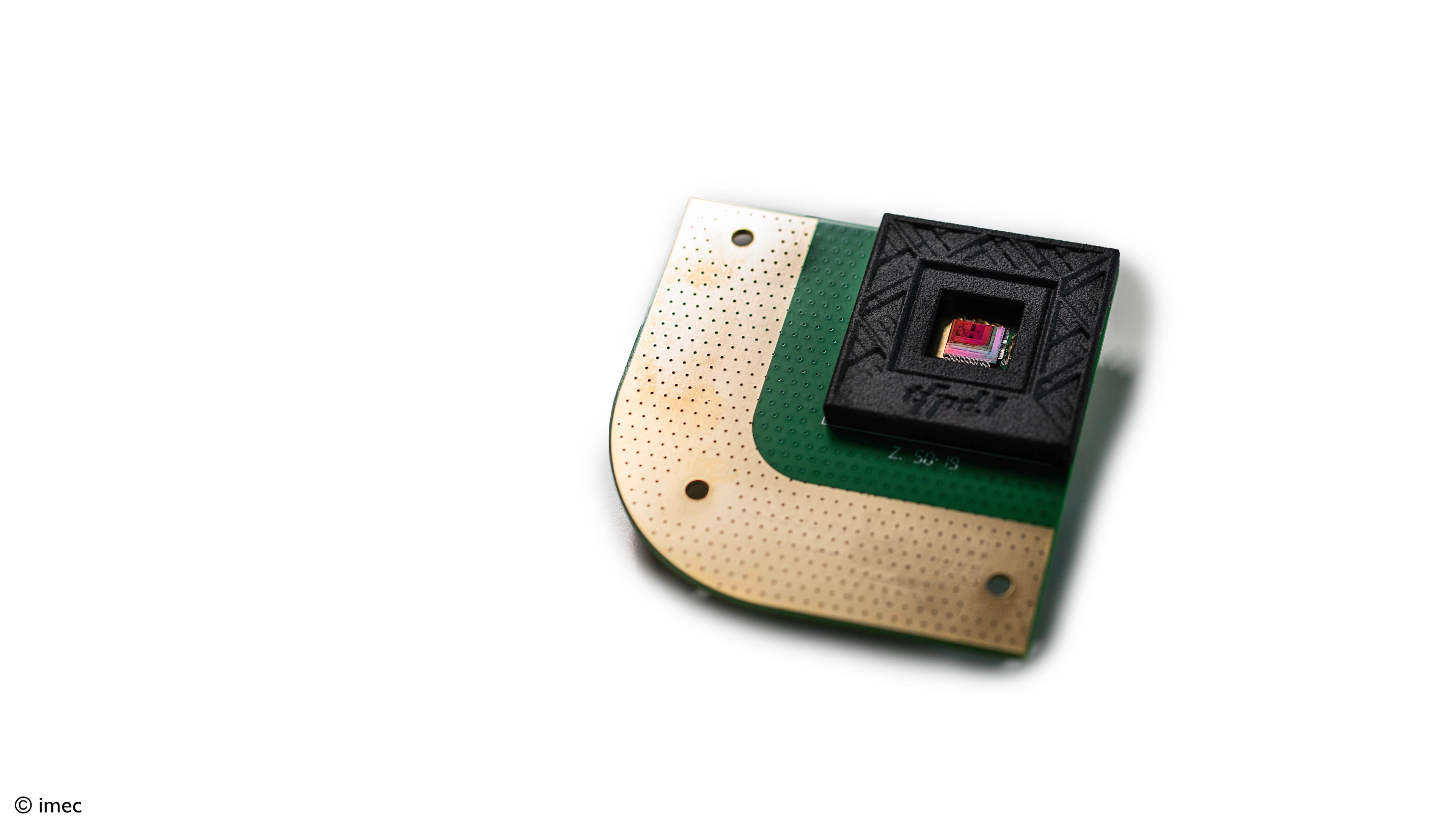

Imec already has a fine record in the area of sensor technology. This research was given an extra boost when the Holst Centre was set up in Eindhoven, 10 years ago now. The program has included producing a sensor module for cardiac and vascular diseases, an adhesive health bandage and an EEG headset as a demonstrator of imec’s unique low-power sensor technology. This sensor technology has also already been picked up by commercial companies to be developed further into actual products.

Examples of some of the demonstrator items developed by imec to illustrate its unique low-power sensor technology.

Imec’s unique sensor technology has also been used already by a number of industrial partners.

What makes this program so unique?

Many companies and research organizations are involved with technology designed to improve our health. What makes imec’s program so unique? Van Hoof: “The depth and breadth of the program is unique anywhere in the world. And the applications it will create will be unique in terms of personalization for both detecting health problems and feedback.”

“By depth I mean the clinically relevant, scientific nature of the data gathered. Our sensors enable us to measure an enormous number of parameters. For example, in the stress test we use a sensor wristband and plaster to measure 3 physiological signals (skin conductance, ECG and temperature), from which we can calculate 20 parameters. In the trials we will typically measure as many signals as possible so that we can then pick out the most relevant parameters for each specific application. The ultimate commercial product that will be developed by our partners may consist of just one sensor and one smartphone app, otherwise it would be too complicated for the user. In addition to our own sensors, we also include commercially available sensors from our partners in the trials.”

“The breadth of the program is also huge. We have psychologists and therapists working with us, as well as people specializing in sensor technology, user interfaces, digital phenotyping, privacy and security. Our work includes establishing living labs and trial organizations and developing the most suitable business models (subscription, hire, prescription by a physician, etc.). Our merger with iMinds has enabled us to expand our knowledge so that we now have a broad package that makes creating a total solution possible. But in the end, the success of the program will depend on the partners we are able to convince to work with us.”

Are you the partner we’re looking for?

As we have said, imec is currently looking for companies willing to work with it on this research program. Van Hoof: “We want to develop an ecosystem that enables us to have all of the areas of expertise on board so that we can develop useful products for our partners to market and sell. Or perhaps interested companies already have products that they can improve on thanks to the results of this program. Because we will be setting up major trials and will be using the living labs methodology, our partners will receive immediate feedback from the end-user about what works and what doesn’t. This means they take much less of a risk when they bring a new product to market.”

So, if you are a company working with sensors, systems or apps relating to health or specific diseases, or if you are a doctor or specialist or coaching company and are interested in imec’s approach, please contact Chris Van Hoof (016/281815).

Want to know more?

- On 16 May, Chris Van Hoof will be speaking in Antwerp at the Imec Technology Forum Belgium. More information from the ITF website.

- In October, imec is organizing ITF Health, an Imec Technology Forum dedicated totally to imec’s healthcare technology. If you would like to attend, you will have to travel to the US. More information from the ITF website.

Chris Van Hoof leads imec’s wearable health R&D across 3 imec sites (Eindhoven, Leuven and Gent). Imec’s wearable health teams provide solutions for chronic-disease patient monitoring and for preventive health through virtual coaching. Chris has taken wearable health from embryonic research to a business line serving international customers. Chris likes to make things that really work and apart from delivering industry-relevant qualified solutions to customers, his work has already resulted in 4 imec startups (3 in the healthcare domain). After receiving a PhD from the KU Leuven in 1992 in collaboration with imec, Chris has held positions as manager and director in diverse fields (sensors, imagers, 3D integration, MEMS, energy harvesting, body area networks, biomedical electronics, wearable health). He has published over 600 papers in journals and conference proceedings and has given over 60 invited talks. He is full professor at the KU Leuven.

Published on:

5 May 2017