Anyone who spends time regularly on a bike knows that cycling can place great strain on the lower back. To counter this, engineers and physical therapists are now joining forces to develop smart bikewear featuring integrated sensors that analyze the rider’s posture. Physios would be able to use the data from the smart jersey to gain greater insight into the back problems suffered by cyclists, while road racers wearing these outfits could monitor and adjust the way they hold their bodies constantly while they are ‘on the go’. So say goodbye to some of those cycling-related injuries!

Pieter Bauwens, Paula Veske and Tom Sterken, respectively a postdoc researcher, doctoral student and R&D engineer at CMST, an imec research group at UGhent, tell us more about these sensors and the way they are incorporated into smart cycling apparel. Joke Schuermans, another postdoc researcher into physiotherapy and rehabilitation sciences at UGhent, explains the link between fitness, fatigue and incorrect posture on a bicycle. But first and foremost: discover how cyclewear with sensors can make a world of difference for (amateur) cyclists.

This cycling outfit is a good example of smart clothing, which is an up-and-coming new technology that we are sure we will be hearing more of in the years to come. The American company SKIIN is forecasting three main trends in the sector for smart textiles.

3 trends in smart clothing

TREND 1. Athletes and fitness fanatics in the box seat

Fitness-wearables and devices that you wear on your body (such as Fitbit devices, Apple Watch, Moov, etc.), will be making way increasingly for biometric T-shirts, sports bras, running shoes and compression sleeves. Because sports enthusiasts are becoming more attached to things such as comfort, design and the accuracy of the readouts. One good product that confirms this trend are the smart yoga pants from Nadi X, which use your smartphone to provide feedback about the correct way to adopt the various positions when doing yoga. But this type of product only records a movement in a particular direction and tells the user nothing about the actual quality of the movements. In the future, such smart garments will get much more accurate and give more detailed data.

TREND 2. Everything talking to everything else

Just as with the Internet of Things, smart clothing will also be able to communicate with the things around us. Which may be of interest if you want to have things such as thermostats, lights, loudspeakers or domestic appliances react to your body temperature, heart rate, brainwaves or movements. For instance, Google has developed a coat (based on the Jacquard platform for intelligent textiles) with which you can use your smartphone and listen to music or incoming messages by simply tapping the bottom of the sleeve. This means that textiles can be used as an interface for operating a device, or else can send (biometric) data to a device, which then carries out a particular action based on that data.

TREND 3. Just what the doctor ordered

Specialists expect the use of smart clothing and textiles to increase enormously in healthcare applications over the next 5 years, including monitoring patients at home. Examples include smart mattresses and mattress covers for detecting whether patients are moving in bed and turning over sufficiently often, which will reduce the risk of pressure sores; light therapy blankets for newborns with jaundice; baby sleep-suits with breathing sensors for helping prevent cot death; vests for detecting the accumulation of fluid in the lungs; smart heated bandages for wounds; stockings that monitor leg volume in edema patients – and so on.

How do you make electronics stretchable and washable?

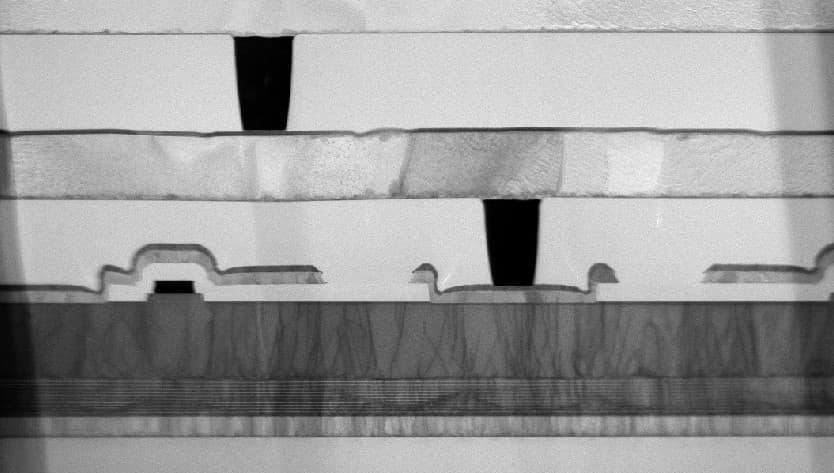

Imec’s CMST lab at UGhent has been working for almost 15 years now on technologies for making electronics stretchable and washable and is a global player in this field. Tom Sterken: “Huge progress has been made over the past 10 years in making chips smaller and thinner. This makes it easier for us to integrate electronic components (microprocessors, sensors, actuators) seamlessly into textiles. Typically, we work with rigid little ‘islands’ of electronics that we connect to stretchable current conductors embedded in a protective film. These conductors have a unique undulating shape that enables the film to be stretched up to twice its length without breaking the conductors. You need a great deal of know-how to connect rigid electronic components to a stretchable current conductor.”

Imec’s CMST lab at UGhent makes smart garments by connecting rigid little ‘islands’ of electronics with stretchable current conductors embedded in a protective film. These conductors have a unique undulating shape that enables the film to be stretched up to twice its length without breaking the conductors.

What smart textiles can mean for cyclists

Amateur cycling has been on the rise as a hobby for years now, partly thanks to events such as the Tour de France and leading cycling stars such as Peter Sagan or Bradley Wiggins. Cycling is also a sport that can be enjoyed at any age. Typically, the age of amateur cyclists ranges from 40 to 70 or even 80. Joke Schuermans: “Often it is somewhat older people or people who are less physically fit who take up cycling. But the very posture required for cycling places great stress on the back, because the lower back adopts an unnaturally rounded or hunched shape for long period of time. This can soon lead to chronic problems. The figures confirm this: up to 80% of cyclists have to deal with lower back problems at some stage. So clearly this is a significant problem.”

Professional cyclists are properly monitored, though, and use bikes that are made exactly to their body measurements. The posture they adopt when they sit on their bikes is closely analyzed and modified. But this is not the case with recreational cyclists and many of them are forced to abandon the sport after numerous visits to their physio.

Joke Schuermans: “In the Nano4Sports project, I have been researching the relationship between movement control, fatigue and lower back problems. Often we see that when cyclists become tired as they make an extra effort on their bike, they exert more movement and stress on their back/upper body and pelvis. This is a natural phenomenon: cyclists try to keep generating the same pedal power despite the fact that their quadriceps are tired and hence they are unable to develop the power they want from the muscles in their upper legs. But this sort of compensating pattern of movement alters the position of their upper body and pelvis and so cyclists run the risk of sustaining repetitive strain injuries. The muscles in the trunk and pelvis have a natural stabilizing function and are not normally used to produce power. This also means that the underlying parts of the body are unable to cope with the mechanical load that goes with the hunching position adopted by cyclists to compensate for their weariness. But if cyclists can be given feedback about their posture while they are riding and are able to correct it, this would make the sport much more comfortable and attractive.”

In the physio’s treatment room

Post-doc researcher Joke Schuermans is now using infrared reflectors for her research that are placed at strategic locations on the body. A camera is then able to map the movements of the body riding a bike and have them analyzed by specific software.

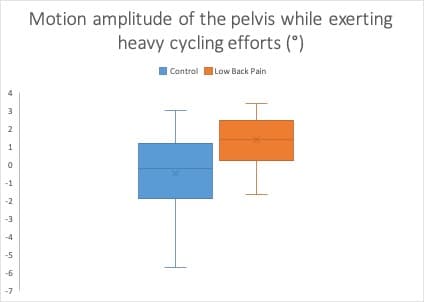

Joke Schuermans: ‘As part of Nano4Sports, I took measurements with some 90 volunteers to gain greater insight into lower back problems among cyclists. I am particularly interested in the link between fatigue, fitness and incorrect posture on a bike. Are people who are less fit more inclined to adopt the wrong position on their bike? Will people who are fitter also find themselves in the wrong position when they become tired after a long ride? In the lab I have them do a fatigue test in which I measure – in addition to their heart rate and wattage – their movement and hence the quality of those movements in relation to intensity and tiredness. Early results from the research show that cyclists who regularly complain of pain in their lower back when on training rides also compensate significantly more with movements in their pelvis than cyclists who are completely free of problems.”

These measurements can only be taken in a lab situation. It is not possible to use them to develop a standalone system that makes it easy for cycling enthusiasts to use during their weekly training rides.

This figure shows that people who regularly complain of lower back pain during training rides (Injury Group) make left-to-right movements of their pelvis to a far greater extent (statistically significant difference with p-value of p = 0.001) than cyclists who never experience problems on their bike.

Of course, there are all sorts of consumer products on the market that claim to measure your posture on a bike. For example, there is the German company LEOMO, which provides a system that costs around €1000. But the feedback it provides is fairly complex. Joke Schuermans: “In actual fact, what we need to do is aim to create a very simple system – a smart cyclist’s tunic would be ideal – that takes accurate measurements and sends them to you on your smartphone or bike computer. The interface can be as uncomplicated as a red and green bar that changes color according to how good your posture on the bike is. That way, cyclists become more aware of their posture and can avoid suffering from chronic problems.”

Prototype of a smart cyclist’s outfit

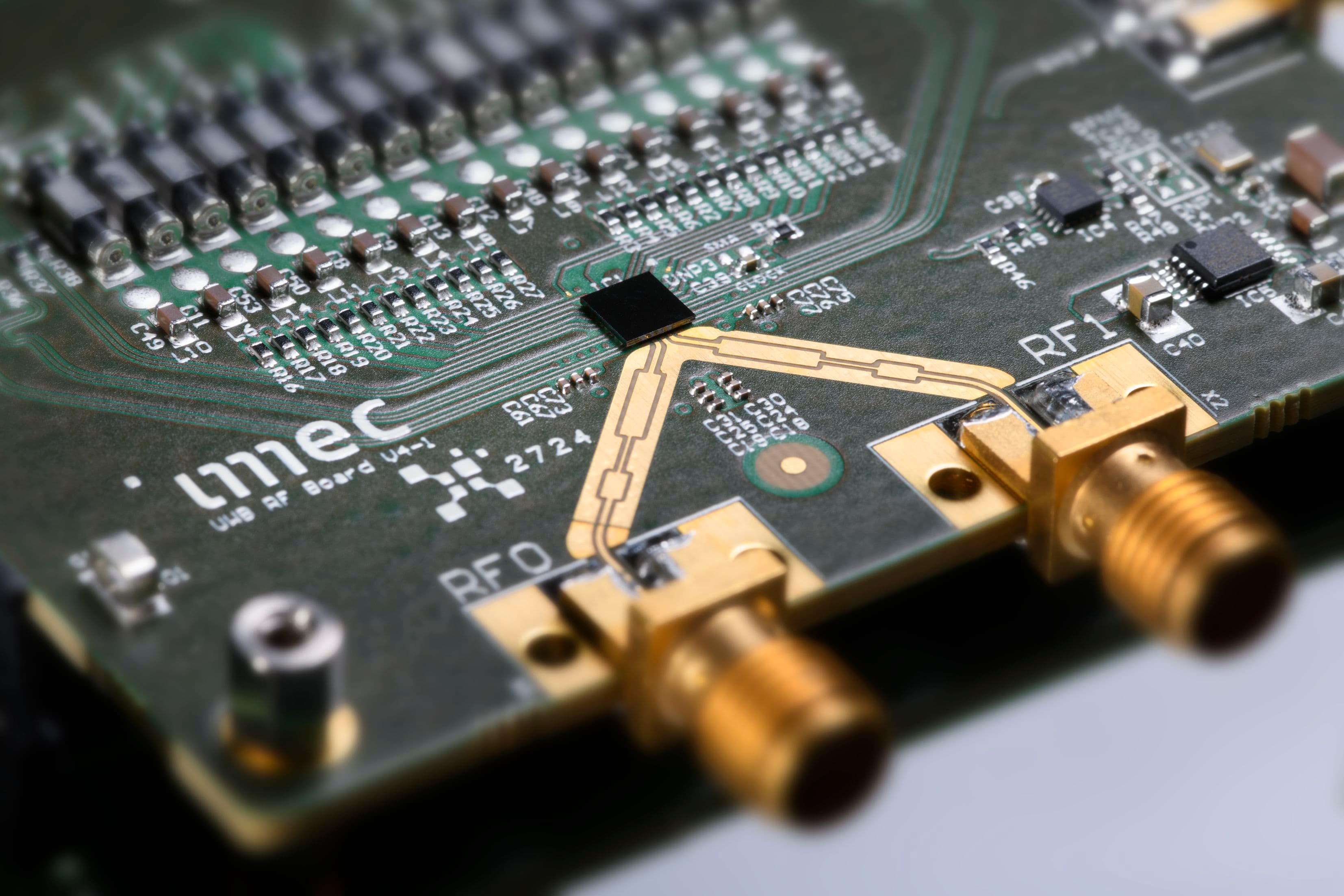

Imec research group CMST, which is also working on the Nano4Sports project, was given the task of developing just such a tunic. Pieter Bauwens: “We used off-the-shelf motion sensors (Bosch BNO055) that measure movements in the X, Y and Z direction. These were positioned at the lower back vertebrae L1, L3, L5 and S1. We also placed 2 sensors on the side to measure movements of the pelvis. The sensor node was adjusted so that it could exchange information with at least 8 other nodes. And all of the nodes were connected with a central microprocessor with Bluetooth functionality that sent the data wirelessly to a smartphone or sports watch. CMST’s flex-stretch technology, as described above, was used for the connections on the clothes.”

The first prototype of the smart cycling suit hides 6 sensors under the textile that measure movement in the X, Y and Z directions. A central module with battery is located at the bottom of the back and can easily be clicked in and out, e.g. for washing.

Paula Veske: “We use a 25µm-thick layer of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) to protect the electronics and incorporate them into the cyclist’s jersey. First, a TPU layer is laminated on the fabric using a heat press (170°C and 4 bar for 20 seconds). This makes the TPU softer and so it adheres to the material. The electronics module is then applied to the TPU layer. Finally, everything is covered with a TPU-laminated piece of fabric before being treated with the heat press again. Because the battery cannot be laminated at the same time (due to the high temperatures involved), a central module with a battery is soldered to the whole thing afterwards. If the system were ever to come on to the market, this central module would probably take the form of a clickable box that can easily be clicked on and off the smart cyclist’s tunic. Being able to do that is also important for washing the shirt and recharging the battery.”

Of course this is still at the prototype stage. Further tests will enable the physical therapist to check whether the readings are as reliable as they are with the standard system. Once that is done, CMST will go looking for companies that want to market a smart cycling tunic of this kind.

Also for the office

Physio Joke Schuermans is already enthusiastic about it: “Wireless sensors will mean huge progress for our research into movement and exercise. At the moment we can already use wireless sensors for muscle tension tests (EMG) in which the sportsperson runs on a treadmill. These types of measurements were impossible previously using wired sensors.

In the world of cycling, almost no research has been conducted yet into movement for the prevention of injuries, apart from posture and movement analysis connected to a dynamic bike-fit procedure. So there are still lots of things we need to find out about making sport healthier and more enjoyable. Having a tape with wireless motion sensors that we can attach to the back would be a major step forward. But cyclists also need to remain aware of their posture on a bike outside the lab – and for that, a smart cycling tunic is the perfect solution.”

“Comparable technology can also be of use in other forms of clothing: in a sports outfit for doing abdominal and back muscle exercises correctly, or in everyday clothes for keeping an eye on our posture when we sit for long hours at the office,” concludes Joke Schuermans.

Want to know more?

- In this article we only talk about one of the applications being developed as part of Nano4Sports. You can find more information about the whole project on the www.nano4sports.eu website. Project Nano4Sports is funded by the Interreg V Flanders-Netherlands program, the cross-border cooperation program with financial support from the European Regional Development Fund. More information: www.grensregio.eu

- Are you interested in further developing this prototype, together with our researchers? Let us know via this contact form.

Paula Veske obtained her textile technologist degree in 2014 at Tallinn University of Applied Sciences while also gaining internship experience at the Adidas Group headquarters in Germany. Later, while working as a textile technologist for a clothing manufacturing company, she gained a Master’s degree from Tallinn University of Technology in 2017, specializing in textile technology. Since then, she has worked in a technical textile production company developing smart textile products and a production line. Projects she has worked on include a smart bra capable of measuring the heart rate, as well as seamlessly integrated electronic textiles. In 2018, Paula joined the Center for Microsystems Technology Group, affiliated with imec and Ghent University, as a PhD student working on smart textiles.

Tom Sterken obtained his master’s degree in microelectronics engineering from Ghent University, Belgium, in 2001. He began working at imec in Leuven on the design, modeling and manufacture of miniature power generators based on MEMS technology. In 2009, he was awarded his PhD degree on the topic at MICAS, K.U. Leuven, Belgium. In 2010, Tom joined the Center for Microsystems Technology Group, affiliated with imec and Ghent University, working on ultrathin chip packaging and stretchable electronics.

Pieter Bauwens graduated from Ghent University in 2006 as an electrical engineer. He began working on his PhD at the same University as part of the CMST research group, an affiliated lab of imec. He designed several chips for intelligent control systems in passive matrix displays. Since achieving his doctorate in 2010, Pieter’s main focus has been on Smart Power ICs and integrated system design.

Joke Schuermans graduated as a sports physiotherapist at the University of Ghent (Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences) in 2012, after which she continued her academic course as a PhD student. Her thesis focused on detecting and preventing the risk of hamstring injury in footballers. After gaining her PhD in 2016, Joke became a postdoctoral researcher involved in analyzing the determinants of injury risk and performance in road cycling in the same department, where she remains today. In addition to her academic endeavors, she also works in clinical practice (RevaMelle, Melle; CTRL-Health, Merelbeke), where she focuses mostly on gait and running analyses, exercise capacity testing and strength and fitness training, as well as (sports) rehabilitation. Joke also runs strength training sessions for the KAA Ghent Ladies Premiere League football team.

Published on:

28 June 2019