Faster, lighter, more durable, and, at the end of the day, also much cheaper: the benefits of photonic circuits are considerable, for a wide range of applications. And the Netherlands plays an important role, globally, in the development and application of this key technology. In recent years, under the leadership of PhotonDelta, a solid foundation has been laid under the Dutch integrated photonics ecosystem. One important application area of this key technology can be found in precision agriculture.

In a world approaching 10 billion people by 2050 and an exponentially rising demand for agricultural products, we cannot do without precision agriculture. In this process, plants or animals receive exactly the treatment they need, determined with great accuracy thanks to a combination of technologies such as robotics and miniaturized biosensors. This allows production to be optimized, leading to more sustainable crops, increased production, and greater food safety: a prerequisite for a future-proof food supply.

Integrated photonics is essential for this. Photonic chips are lighter, smaller, and therefore more scalable than other solutions. Sensor systems running on integrated photonics ensure that in the agricultural sector and food industry all requirements regarding safety, health and sustainability can be met.

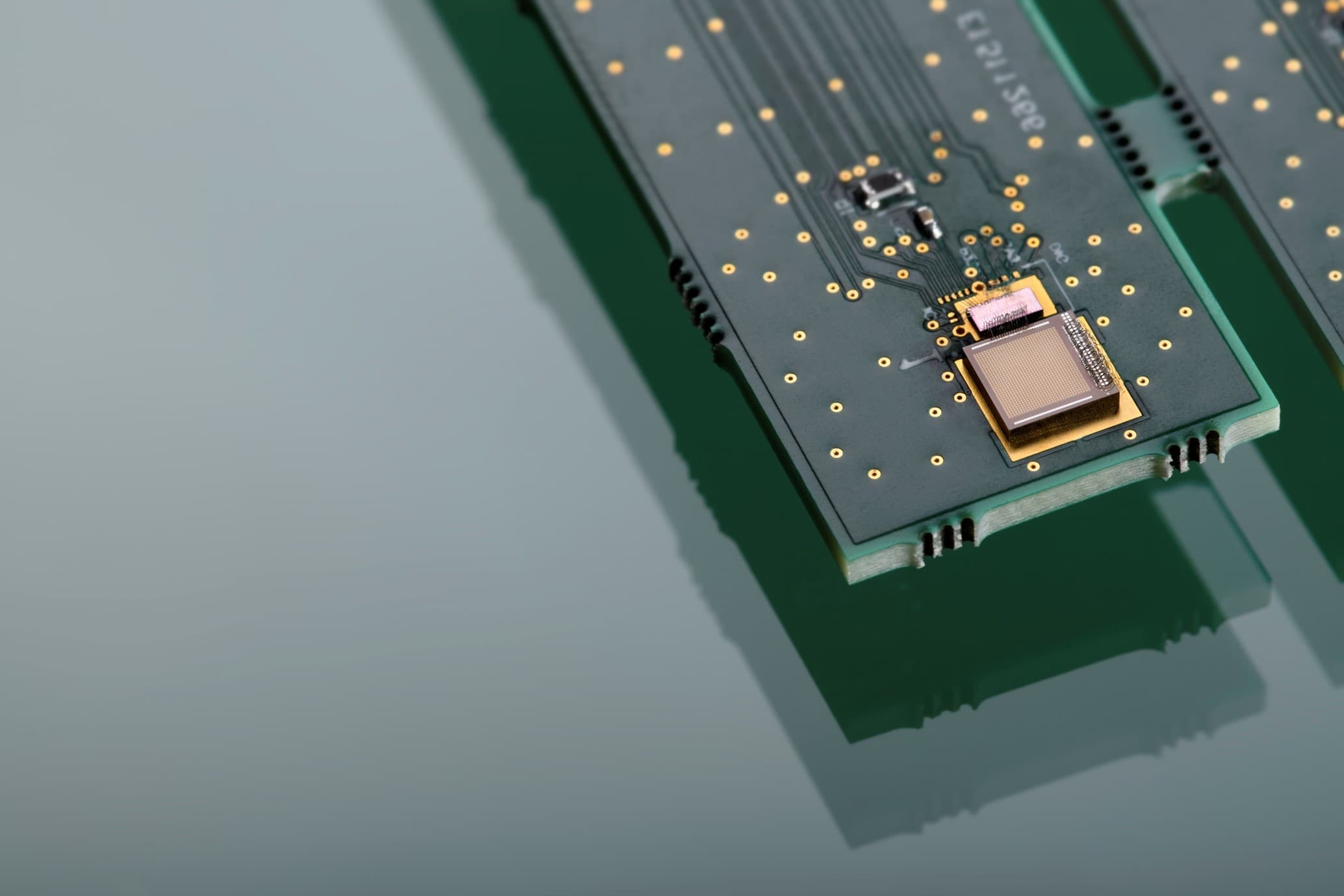

What is integrated photonics?

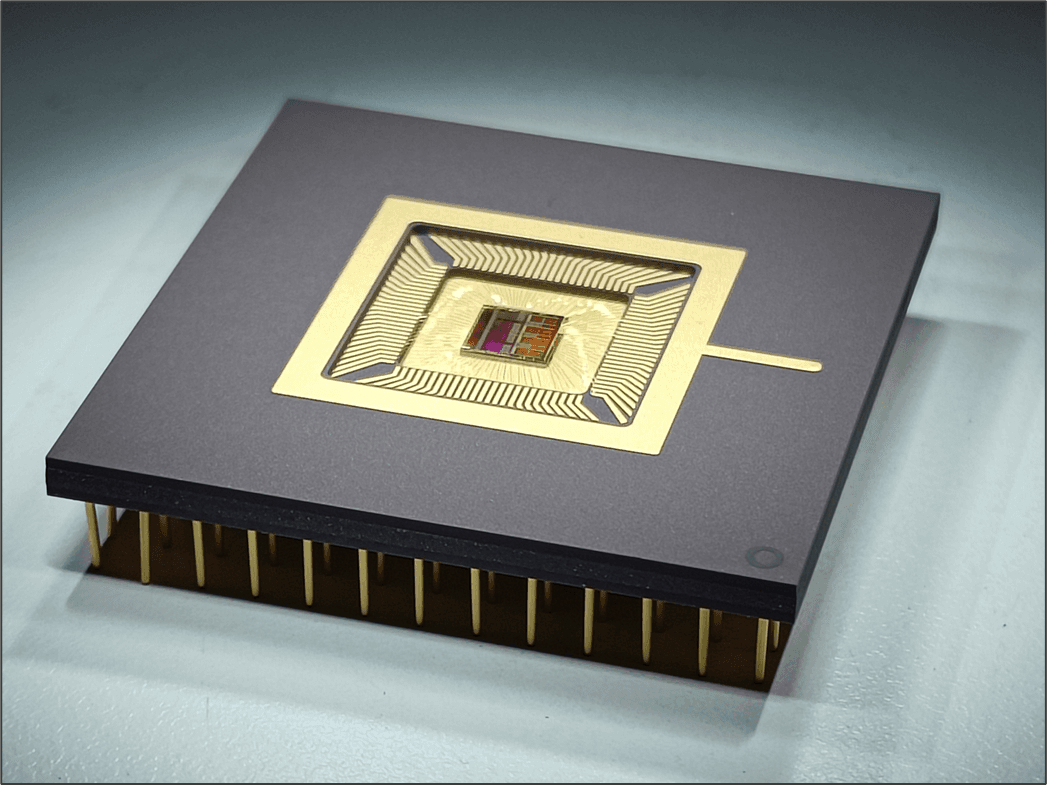

Photonic technology detects, generates, transports, and processes light. Current applications include solar cells, sensors, and fiber-optic networks. Photonic chips, officially called Photonic Integrated Circuits (PICs), integrate various photonic and often electronic functions into a microchip to make smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient devices. Because they are manufactured like traditional chips (with wafer-scale technology), mass production is also within reach - with price drop as a result.

The Netherlands has now built up considerable experience with integrated photonics in precision agriculture. Harrij Schmeitz, director of the Fruit Tech Campus in Geldermalsen, sees the evidence every day. "There are huge opportunities for photonics in agrifood if we can translate the technology into practical applications that allow the state of the product to be examined on both the outside and the inside."

He cites an example of integrated photonics at fruit grower Fruitmasters in Geldermalsen: "They use relatively simple cameras to take 140 pictures in milliseconds of every apple that passes on the sorting belt. This is done in 3D, fully automatically. The system removes the bad apples before they are packed for the customers. That used to be done manually, so that's a big improvement."

Farmers today record a lot of data, which enables them to plan ahead and learn to give plants exactly the right amount of water, light, and nutrients at the right time. Sensors with photonic chips not only ensure that the data becomes available, but also that the farmer can then use it to better treat his crops or animals. The first robot that uses camera technology to determine how much to spray the crop has also been introduced. It calculates the needs very quickly when it passes by the crop."

According to Schmeitz, photonics in the agrifood sector will bring about a change to plant-controlled and tree-controlled cultivation. "With LED lighting you can stimulate crop growth in greenhouses. By using different colors you can accelerate that. In the Westland region, you can see purple greenhouses, because a plant grows better on red and blue light. As a result, you can also use less light, which results in savings for the farmer.

Sustainable production

Research into the application of photonics in agrifood takes place throughout the Netherlands, for example in Wageningen at OnePlanet Research Center (a collaboration between WUR, Radboud University, and imec) and at TU Eindhoven.

In Wageningen, Lex Oosterveld and Peter Offermans conduct research into the use of photonics in the food industry and in the cultivation of fruit and vegetables. Oosterveld: "Our technological innovations are aimed at the sustainable production of nutritionally high-quality food and at combating food waste. We are therefore developing technology with which the product quality of food can be measured directly, without it having to be analyzed in a laboratory. This allows us to adjust the production process directly." An example is measuring glucose during fermentation processes or in fruit. "The next step is for this to be done fully automatically based on real-time data. In this way, we optimize the production process, and food waste is avoided."

Nitrogen

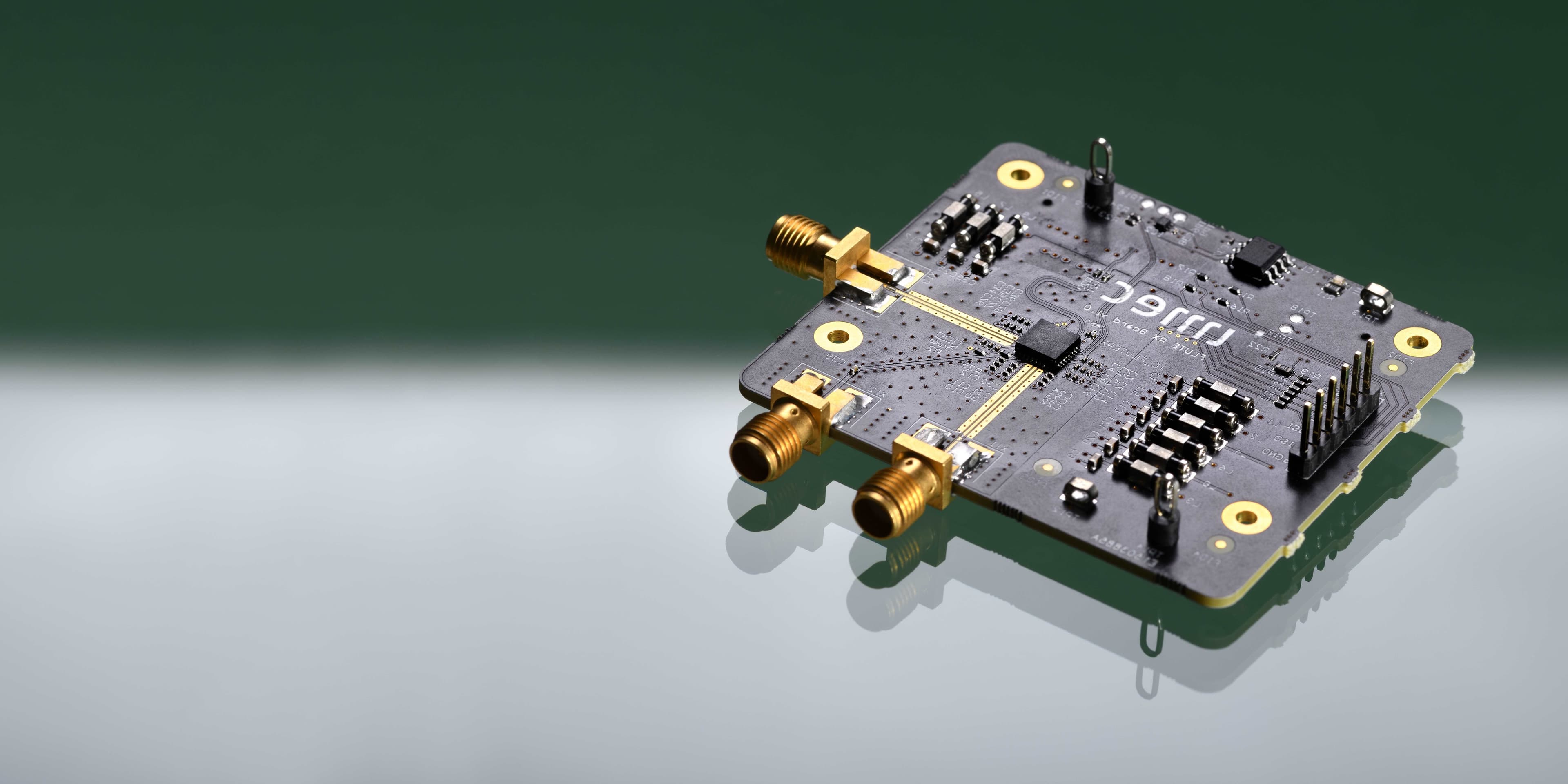

OnePlanet Research Center is also focusing on the nitrogen issue by developing sensor systems to measure the environmental impact in and around cities, such as in companies and stables. Offermans: "It is important to accurately map the emission of nitrogen so that you can reduce emissions based on this data. To this end, we have developed a prototype sensor that allows us to measure the amount of nitrate, an indicator of the presence of nitrogen, in water via the light of different wavelengths." This sensor runs on optical chips.

Photonic measuring systems are also relevant for the cultivation of fruit and vegetables. Offermans: "An example is ripeness monitoring, which helps the product to be harvested at the optimal moment. This process makes sure the product has an optimal quality at the time of consumption and food loss is prevented. Sensors based on integrated optical circuits fit very well into applications in the agrifood sector, as they are suitable for miniaturization, for combining different sensor types, and for the scalable production of our measurement solutions."

Tomatoes and cow's milk

It is no coincidence that the elements that, according to Oosterveld and Offermans, make integrated photonics so important, also come together in the solutions of start-up MantiSpectra. Using PICs that are small, robust, scalable, and customized, this TU Eindhoven spinoff produces sensors that can help determine the health of animals and plants.

CEO Maurangelo Petruzzella and his team have developed a practical application for this purpose. "From the outside of fruits and vegetables, you often can't tell the best time to harvest. Farmers can rely on years of experience and on their instincts, but anything can go wrong. If you pick too early, the product may not have reached its maximum flavor; if you pick too late, spoilage can occur. Photonics is a good tool for this."

With MantiSpectra, after many years of research, Petruzzella and several colleagues have developed an optical chip that uses infrared light to monitor the ripeness of tomatoes. "We want to develop this chip into a handy device that horticulturalists can use to go into the greenhouse and check individual tomatoes, even before their harvest. Until now, you have to pick a tomato and cut it open to check its freshness. If it is ripe, you have cut into it unnecessarily. The same applies, of course, if it is not yet ripe. Then it's better to leave it on the plant."

But it's not just about fruit. For example, the sensor is also suitable for checking the quality of unpasteurized milk and whether cows have health problems. The MantiSpectra chip sensor detects infrared light and can use an algorithm to quickly determine whether the milk is good. Not only is this more accurate and faster, but it also avoids all kinds of additional costs that go into complicated traditional quality checks and wasting good milk. "The problem is that the quality of milk is usually only measured during its processing", Petruzzella explains. "If you are able to measure this directly at the farmers, then you will also know what the health status of the cow is."

Research, production, and applications

What Maurangelo Petruzzella is showing with MantiSpectra is a good example of the many applications that integrated photonics has to offer. It is precisely the combined strength in both primary research and in production and uses for specific applications that currently make the Netherlands one of the global centers in photonics. The mission-driven innovation policy is visible in it, both at the level of the individual farmer and for the sustainability ambitions of our planet. The Netherlands has everything it needs to retain that leading role, including in the food technology sector. But for this, some follow-up steps are necessary, says PhotonDelta director Ewit Roos. These include investments in research, the construction of larger foundries (wafer factories), and help for promising start-ups. "In this way, we can stay ahead of the competition and strengthen Europe's intended strategic autonomy in integrated photonics."

That will require a long haul, though. Oosterveld and Offermans expect that it will take another five years or so before the major photonics breakthrough occurs in the agricultural sector and another ten years or so before it happens in the food industry. Oosterveld: "There, it often involves complicated industrial processes that are less easy to adapt, which is why the breakthrough there will take a little longer."

In the meantime, the Dutch integrated photonics sector is ready for the next phase: further industrialization, in which scaling up (or: cost reduction per PIC) and integration on the existing large production platforms of the semiconductor industry are key. For Ewit Roos, this development is clear: "The world sees this potential and is investing in it. As an ecosystem, but also in a European context, we are of course anticipating this by excelling and concentrating on what we are good at. That way, we secure a position in those global value chains and are an attractive location for initiatives that want to join them."

Sensoren met geïntegreerde fotonica als sleutel voor onze voedselgarantie, ook in de toekomst

De wereldbevolking groeit exponentieel. Precisielandbouw die draait op geïntegreerde fotonica draagt bij om onze voedselvoorziening ook op termijn veilig en duurzaam te houden.

Sneller, lichter, duurzamer en onder aan de streep uiteindelijk ook goedkoper: de voordelen van geïntegreerde fotonica zijn aanzienlijk, voor een breed scala aan toepassingen. En Nederland speelt mondiaal een belangrijke rol in de ontwikkeling en toepassing van deze sleuteltechnologie. De afgelopen jaren is onder aanvoering van PhotonDelta een stevig fundament gelegd onder het Nederlandse geïntegreerde fotonica ecosysteem. Eén belangrijk toepassingsgebied van deze sleuteltechnologie is te vinden in de precisielandbouw.

In een wereld bijna 10 miljard mensen in 2050 en een exponentieel stijgende vraag naar landbouwproducten kunnen we niet zonder precisielandbouw. Daarbij krijgen planten of dieren precies de behandeling die ze nodig hebben, met grote nauwkeurigheid bepaald dankzij een combinatie van technologieën zoals robotica en geminiaturiseerde biosensoren. Hierdoor kan de productie worden geoptimaliseerd, wat leidt tot duurzamere gewassen, verhoogde productie en een grotere voedselveiligheid: een absolute voorwaarde voor een toekomstbestendige voedselvoorziening.

Geïntegreerde fotonica is daarbij essentieel. Fotonische chips zijn lichter, kleiner en daardoor schaalbaarder dan andere oplossingen. Sensorsystemen die draaien op geïntegreerde fotonica zorgen er in de agrarische sector en de levensmiddelenindustrie voor dat aan alle eisen rond veiligheid, gezondheid en duurzaamheid kan worden voldaan.

Wat is (geïntegreerde) fotonica?

Fotonische technologie detecteert, genereert, transporteert en verwerkt licht. Huidige toepassingen zijn onder meer te vinden in zonnecellen, sensoren, camera’s, LEDs en glasvezelnetwerken. Fotonische chips integreren verschillende fotonische en vaak elektronische functies in een microchip om kleinere, snellere en energiezuinigere apparaten te maken. Omdat ze gefabriceerd worden als traditionele chips (met wafer-scale technologie), is ook massaproductie binnen bereik - met prijsdaling als gevolg.

Nederland heeft inmiddels veel ervaring opgebouwd met geïntegreerde fotonica in de precisielandbouw. Harrij Schmeitz, directeur van de Fruit Tech Campus in Geldermalsen, ziet er dagelijks de bewijzen van. “Er zijn enorme kansen voor fotonica in de agrifood als we de technologie kunnen vertalen naar praktische toepassingen waarmee zowel aan de buiten- als de binnenkant de staat van het product kan worden onderzocht.”

Hij noemt een voorbeeld van geïntegreerde fotonica bij fruitteler Fruitmasters in Geldermalsen: “Daar maken ze met op zich relatief simpele camera’s in milliseconden 140 foto’s van elke appel die passeert op de sorteerband. Dat gebeurt in 3D, volautomatisch. Het systeem haalt de slechte appels eruit, voordat ze verpakt worden voor de afnemers. Vroeger gebeurde dat handmatig, dus dat is een hele verbetering.”

Boeren leggen tegenwoordig veel data vast, die de boer in staat stelt vooruit te plannen en te leren om planten op het juiste moment precies de juiste hoeveelheid water, licht en voedingsstoffen te geven. Sensoren met fotonische chips zorgen er niet alleen voor dat de data beschikbaar komt, maar ook dat de boer deze vervolgens kan inzetten voor een betere behandeling van zijn gewassen of dieren. Ook is inmiddels de eerste robot geïntroduceerd die met behulp van cameratechnologie zelf bepaalt hoeveel hij het gewas moet bespuiten. Die rekent dat razendsnel uit als hij langs het gewas rijdt.”

Volgens Schmeitz brengt fotonica in de agrifoodsector een omslag teweeg naar plantgestuurd en boomgestuurd telen. “Met ledverlichting kun je in kassen de groei van het gewas stimuleren. Door het gebruik van verschillende kleuren kun je dat versnellen. In het Westland zie je paarse kassen, want een plant groeit beter op rood en blauw licht. Daardoor hoef je ook minder licht te gebruiken wat een besparing voor de teler oplevert.

Duurzaam produceren

Op diverse plaatsen in Nederland vindt onderzoek plaats naar de toepassing van fotonica in de agrifood, bijvoorbeeld in Wageningen bij OnePlanet Research Center (een samenwerking van WUR, Radboud Universiteit en imec) en op de TU Eindhoven.

In Wageningen doen Lex Oosterveld en Peter Offermans onderzoek naar het gebruik van fotonica in de levensmiddelenindustrie en bij de teelt van groenten en fruit. Oosterveld: “Onze technologische innovaties zijn gericht op het duurzaam produceren van nutritioneel hoogwaardig voedsel en het tegengaan van voedselverspilling. Daarom ontwikkelen we technologie waarmee de productkwaliteit van voedsel direct kan worden gemeten, zonder dat het in een laboratorium geanalyseerd hoeft te worden. Daardoor kunnen we het productieproces direct bijsturen.” Een voorbeeld is het meten van glucose tijdens fermentatieprocessen of in fruit. “De volgende stap is dat dit op basis van realtime data volautomatisch gebeurt. Daarmee optimaliseren we het productieproces en wordt voedselverspilling vermeden.”

Stikstof

OnePlanet Research Center richt zich ook op de stikstofproblematiek door de ontwikkeling van sensorsystemen om de milieu-impact in en om steden te meten, zoals in bedrijven en stallen. Offermans: “Het is belangrijk om de emissie van stikstof nauwkeurig in kaart te brengen, zodat je op basis van deze data de uitstoot kunt reduceren. Daarvoor hebben we een prototype van een sensor ontwikkeld waarmee we de hoeveelheid nitraat, een indicatie voor de aanwezigheid van stikstof, via licht van verschillende golflengtes in water kunnen meten.” En inderdaad: die sensor draait op optische chips.

Ook voor de teelt van groenten en fruit zijn fotonische meetsystemen relevant. Offermans: “Een voorbeeld is het meten van rijpheid van fruit, zodat het product op het optimale moment geoogst kan worden en het product op het moment van consumptie een optimale kwaliteit heeft en voedselverlies wordt voorkomen. Sensoren gebaseerd op geïntegreerde optische circuits lenen zich goed voor toepassingen in de agrifood sector, omdat ze geschikt zijn voor miniaturisatie, het combineren van verschillende sensortypen en voor het schaalbaar produceren van onze meetoplossingen.”

Tomaten en koeienmelk

De elementen die geïntegreerde fotonica volgens Oosterveld en Offermans zo belangrijk maken, komen niet toevallig ook samen in de oplossingen van start-up MantiSpectra. Met PICs die klein, robuust, schaalbaar en op maat gemaakt zijn produceert deze spinoff van de TU Eindhoven sensoren die kunnen helpen bij het bepalen van de gezondheid van dieren en planten.

CEO Maurangelo Petruzzella heeft daartoe met zijn team een praktische toepassing ontwikkeld. “Aan de buitenkant van groenten en fruit kun je vaak niet zien wat het beste moment is om te oogsten. Landbouwers kunnen vertrouwen op jarenlange ervaring en op hun instinct, maar er kan van alles misgaan. Als je te vroeg plukt, hebben de producten misschien nog niet hun maximale smaak bereikt, als je te laat plukt kan er bederf optreden. Fotonica is hierbij een goed hulpmiddel.”

Met MantiSpectra heeft Petruzzella na vele jaren van onderzoek met enkele collega’s een optische chip ontwikkeld die met infrarood licht de rijpheid van tomaten controleert. “We willen deze chip uitbouwen tot een handzaam apparaatje waarmee tuinbouwers de kas in kunnen gaan en de afzonderlijke tomaten kunnen controleren, dus nog voor de oogst. Tot nu toe moet je een tomaat plukken en opensnijden om de versheid te controleren. Als hij dan rijp is, heb je er onnodig in gesneden. Dat geldt uiteraard ook voor als hij nog niet rijp is. Dan kun je hem beter aan de plant laten hangen.”

Maar het gaat niet alleen om fruit. De sensor is bijvoorbeeld ook geschikt om de kwaliteit van ongepasteuriseerde melk te controleren en na te gaan of koeien gezondheidsproblemen hebben. De MantiSpectra chip-sensor detecteert infrarood licht en kan met behulp van een algoritme snel vaststellen of de melk wel goed is. Dat is niet alleen secuurder en sneller, maar het voorkomt ook allerlei extra kosten die opgaan aan ingewikkelde traditionele kwaliteitscontroles en verspilling van goede melk. “Het probleem is dat de kwaliteit van de melk meestal pas wordt gemeten tijdens de verwerking ervan,” legt Petruzzella uit. “Als je in staat bent om dit direct bij de boeren te meten, dan weet je ook wat de gezondheidsstatus van de koe is.”

Onderzoek, productie en toepassingen

Wat Maurangelo Petruzzella met MantiSpectra laat zien is een goed voorbeeld van de vele toepassingen die de geïntegreerde fotonica te bieden heeft. Juist de gecombineerde kracht in zowel het primaire onderzoek als in de productie en het gebruik voor specifieke toepassingen maken Nederland op dit moment tot een van de centra in de mondiale fotonica. Het missiegedreven innovatiebeleid wordt erin zichtbaar, zowel op het niveau van de individuele boer als voor de duurzaamheidsambities van onze planeet. Nederland heeft, óók in de foodtech-sector, alles in zich om die leidende rol te behouden. Maar daarvoor zijn wel ook wat vervolgstappen nodig, zegt PhotonDelta-directeur Ewit Roos. Denk daarbij aan investeringen rond onderzoek, de bouw van grotere foundries (wafer-fabrieken) en hulp aan beloftevolle start-ups. “Op die manier kunnen we de concurrentie vóór blijven en de beoogde strategische autonomie van Europa op geïntegreerde fotonica versterken.”

Dat vergt wel een lange adem. Oosterveld en Offermans verwachten dat het nog zo’n vijf jaar zal duren voordat de grote fotonische doorbraak in de agrarische sector plaatsvindt en nog zo’n tien jaar voordat dit gebeurt in de levensmiddelindustrie. Oosterveld: “Daar gaat het vaak om gecompliceerde industriële processen die minder makkelijk zijn aan te passen, vandaar dat de doorbraak daar wat langer op zich zal laten wachten.”

De Nederlandse geïntegreerde fotonicasector staat intussen klaar voor de fase van verdere industrialisatie, waarbij schaalvergroting (ofwel: kostenverlaging per PIC) en integratie op de bestaande grote productieplatformen van de semiconductor industrie aan de orde zijn. Voor Ewit Roos is die ontwikkeling duidelijk: “De wereld ziet deze potentie en investeert daarin. Wij als ecosysteem maar ook in Europees verband, sorteren daar natuurlijk op voor door te excelleren en ons te concentreren op waar goed in zijn. Zo verzekeren we ons van een positie in die wereldwijde waardeketens en zijn we een aantrekkelijke vestigingsplaats voor initiatieven die zich daarbij willen aansluiten.”

Published on:

5 April 2022