Kris Van De Voorde, innovation program manager at imec, talks about the pleasure of building bridges, as well as the enthusiasm among companies in the Flemish food industry for trialing and applying cutting-edge technology. A good example is the hyperspectral camera, which is capable – among other things – of determining the quality of coffee beans, a subject close to Kris’ heart.

Bringing two worlds together

Kris Van De Voorde: “In the past, the quality of food was checked in the main by trained staff, using the naked eye. But in recent years, the food industry has introduced all kinds of new technologies for improving and automating quality inspection processes, as well as the processing and packing of food. The tools used now include optical measuring equipment and digital cameras that look for defects in shapes and colors.”

This automation has helped put the Flemish food industry at the top in terms of employment, growth and innovation. But the sector aims to go even further; it can see plenty of opportunity for improving quality even more and for introducing new products. Chances are, the industry will find the technology needed to do this very close to home: imec and other Flemish research centers have new technologies under development that will make it easier to see, inspect or sort products with an even greater accuracy.

Kris Van De Voorde agrees: “My interest in the food industry began around 7 years ago. By talking to people I became aware that there was a great deal of interest within the industry for trying out new things. I also knew that imec researchers were working on all kinds of smart new sensors. The way I saw it, they were building technology that could readily be applied in the food industry.”

Kris made it his ambition to bring the two worlds together – the food industry and the R&D groups. “I talked with managers in the sector,” he continues, “particularly with Flanders’ FOOD, the umbrella organization for companies in the food sector. This kicked off an initial project: Intelligence for Food, a two-year process to examine the need in the food industry for hi-tech applications. Because this project exposed a clear need, we then began the Sensors for Food project five years ago. This project in turn has been so successful that we have just launched its successor: i-Fast.”

Steven Van Campenhout, project manager for Flanders’ FOOD puts it this way: “Combining microtechnology and nanotechnology with the food sector is by no means obvious, because they seem to be worlds apart. And yet that’s exactly what imec succeeded in doing with the Sensors for Food project. The result is new sensor technology that makes all the difference in food quality control, enabling our food companies in Flanders to excel even more in terms of quality.”

All the colors of coffee

In the meantime, Kris Van De Voorde has spoken with dozens of company managers and food specialists. Sometimes he has to convince them of the possibilities provided by a new development, but usually he meets people who are even more enthusiastic and who are involved in creating new, unexpected applications. Some of these meetings are planned, while other contacts come about by accident. “One day I was talking to the people from The Java Coffee Company from Rotselaar, which operates a much-appreciated coffee bar at imec. They were telling me that to be able to guarantee a constantly high quality of coffee, they have to closely monitor the quality of the coffee beans on a continuous basis. That can be done by measuring the level of roasting of the coffee beans. At the time, the procedure was to regularly take a sample of the beans, grind them and then measure two infrared wavelengths at a specific point of the sample. Preparing the sample is a particularly labor-intensive process and the measuring itself requires a high level of accuracy in order to avoid making mistakes. I thought that this would be an ideal case for examining whether a hyperspectral camera might achieve better results.”

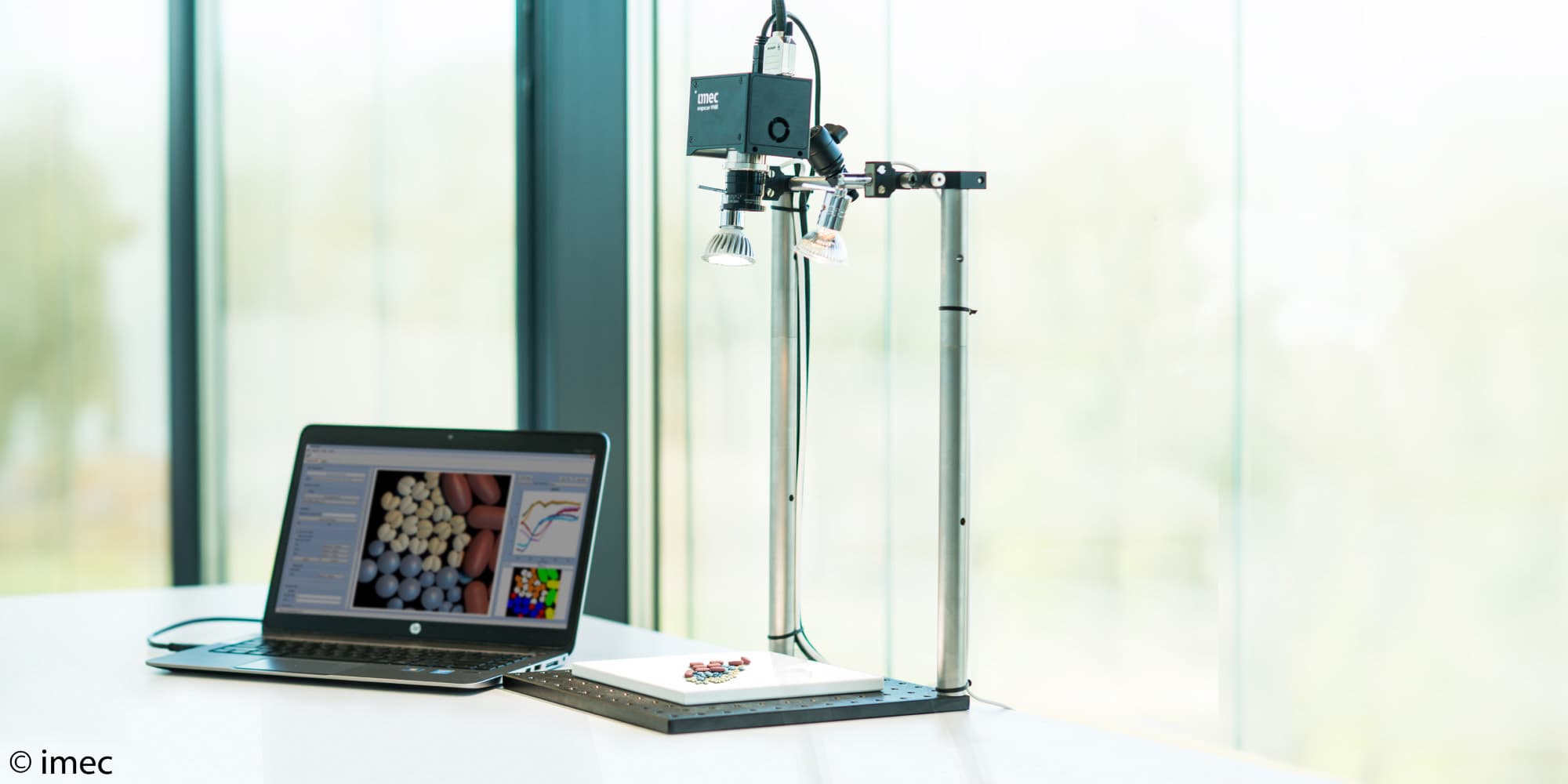

Just as our own eyes do, digital cameras break the light into three bands: red, green and blue. Hyperspectral cameras surpass them: they break the light into dozens, sometimes even hundreds of narrow bands. The result is a spectral signature for each pixel in the image.

“With a hyperspectral camera you can make things visible that are invisible to our own eyes,” says Van De Voorde. “You can identify materials, such as foreign objects that do not belong in a product, or fungi. You can screen the composition of products to find their content in moisture, sugar, fat or protein. You can also check the quality and composition of surfaces and packaging. Plus there are possibilities in terms of hygiene screening. By using line-scanners, this technology is also particularly well suited for incorporating into transport or sorting lines.”

However, until recently, hyperspectral equipment was too expensive, complex and cumbersome to be implemented in the manufacturing process. Imec was the first to succeed in replacing the set of optical components with a single filter on top of a digital image sensor, a filter that can be produced using chip process technology. This process is extremely accurate, compact and also relatively cheap in mass production.

Compact camera with built-in hyperspectral technology

Els Stulens, quality manager at Java: “The big advantage for us is that this new analysis technology enables you to precisely determine the level of roasting on individual intact beans. So there is no need to grind the beans any more. This is because the measurement is carried out within a wide spectrum range – something that is not possible with the two wavelengths currently used. This technology can also be integrated inline, i.e. at the end of the coffee-roasting process, before the coffee goes to the storage silos. If the technology is to break through, one crucial point will be the cost of the hyperspectral cameras, which have only been on the market since last year.” Els believes that system integrators could be an interesting party to work on the marketing of the image-processing technology, since they are able to provide a total solution that may generate a sufficient level of demand to obtain an attractive cost.

Sensors for food

Kris Van De Voorde: “Hyperspectral imaging is one of the three technologies that we highlighted in the Sensors for Food project. This happened after an in-depth survey of the food companies, a survey that put forward a whole range of technologies and asked the companies to estimate possible benefits. Our second focus was on sensors based on millimeter waves – radio waves with interesting characteristics in terms of absorption and resolution – as part of a collaborative program with the VUB. The third technology involved biosensors based on optical fibers, which they are researching at KU Leuven. Each time, we do not put forward an application or development by a single R&D group, but instead we work with various research partners and then compare their applications and capabilities.”

As part of the project, the participating companies presented cases in which the technology was tested. “Java is a typical example of how we have built bridges in recent years between specific food companies and technology development,” says Van de Voorde. “But in addition to guiding these cases we also set up a genuine platform. A platform for networking and partner-matching between food companies and technology providers, complete with a technology watch and monitoring of innovative ideas. We also have a central point of contact to which companies can come with their questions, including technical ones, about what the best innovative sensors would be for them.”

Jan Robrechts is CEO of Lavetan, a laboratory for the food industry. He is extremely positive about this collaboration: “Taking part in the IWT-backed (now VLAIO) Sensors For Food platform gave me the opportunity to keep abreast of existing, new and upcoming sensors. This community enabled me to establish new contacts and explore new opportunities in the food industry.”

Measuring quality on the workfloor

Surveys conducted among food companies show that one of the urgent needs is to introduce more inspection systems on the workfloor and on the production lines. One example is Java, where quality inspection currently takes place offline, on specially prepared samples in a laboratory environment. Being able to analyze samples during production would be more efficient, since continuous measurements could be taken. It would be more reliable, too.

“That’s why we set up a follow-up project for Sensors for Food based on innovative, faster, more efficient and more user-friendly screening systems that can be implemented in-factory by the food companies themselves,” says Kris Van De Voorde. “Hence the name of the project: i-Fast (in-factory food analytical systems and technologies). We will be involved on this for the next four years, until 2020, with the valued support of VLAIO, which is funding the project to a large extent.”

Like its predecessor, i-Fast will be a platform for networking, service provision and advice, based mainly around three technologies. The first, X-FAST, will involve R&D by KU Leuven into the internal quality of porous food that can be measured using X-ray tomography. FYSTEM (UGent) is evaluating the application of non-invasive physical structure definition of food emulsions using high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance. MOBISPEC, finally, is the follow-up project relating to hyperspectral technology. Based on the R&D conducted at imec and KU Leuven, work will be carried out on portable spectral analysis for the workfloor, looking at options such as dot spectroscopy and spectral cameras.

Eating well at Flanders’ FOOD

Kris Van De Voorde: “At imec I am part of the imec interact group. Our aim is to build bridges between Flemish industry, particularly involving SMEs, and the results of the research going on at imec. By working with Flanders’ FOOD we do not have to contact each individual company, but instead can approach the sector as a whole. Flanders’ FOOD is also an ideal partner for us, because it has set itself the aim of promoting innovative solutions for quality control and process improvement in the sector.

As a clincher for the Sensors for Food project and also as a steppingstone to the new i-Fast project, we are inviting anyone interested to an event on 23 March in De Montil, Affligem (10.00 am-4.00 pm). If you come, you’ll hear about the results from the previous project and the possibilities provided by the new one. And while you are there, you will also be able to talk to all of the other participants and managers, as well as sound them out about your own ideas or projects. And because the organization is in the hands of Flanders’ FOOD, the food will be particularly good – yet another good reason for taking part!”

The Sensors for Food-team (left to right) Veerle De Graef - Kris Van de Voorde - Steven Van Campenhout - Bart De Ketelaere - Steven Vermeir

Imec collaborates in many projects (EU, ESA and VLAIO/IWT) on which we work in close collaboration with industrial and academic partners.

Published on:

31 May 2016