Normal life is virtually impossible for most dialysis patients. In addition to the constant discomfort and fatigue, there is the need to spend hours at the hospital on dialysis several times a week. But there is light at the end of the tunnel: the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Nierstichting) is currently working with researchers from imec and others at the Eindhoven-based Holst Centre to develop a portable artificial kidney. This compact dialysis device - which fits into a cabin suitcase - could already make the lives of kidney patients around the world a lot more bearable. But the ultimate goal of these researchers lies one step further: the development of an implantable artificial kidney that could eventually make the invasive treatment of kidney dialysis completely redundant.

It is still difficult to put a precise deadline on it, but the progress so far shows that it is a realistic ambition, says Fokko Wieringa, responsible for research into the artificial kidney at imec. The more compact solution that the Kidney Foundation plans to present before the end of the year is the first step, he says. "But in the meantime, for the longer term, we are already working towards a device so small that it can eventually be implanted." The role of the electric blood pump - essential in a traditional dialysis machine - would then be taken over by the heart and the waste products would leave the body through the urine, just like a real kidney would operate.

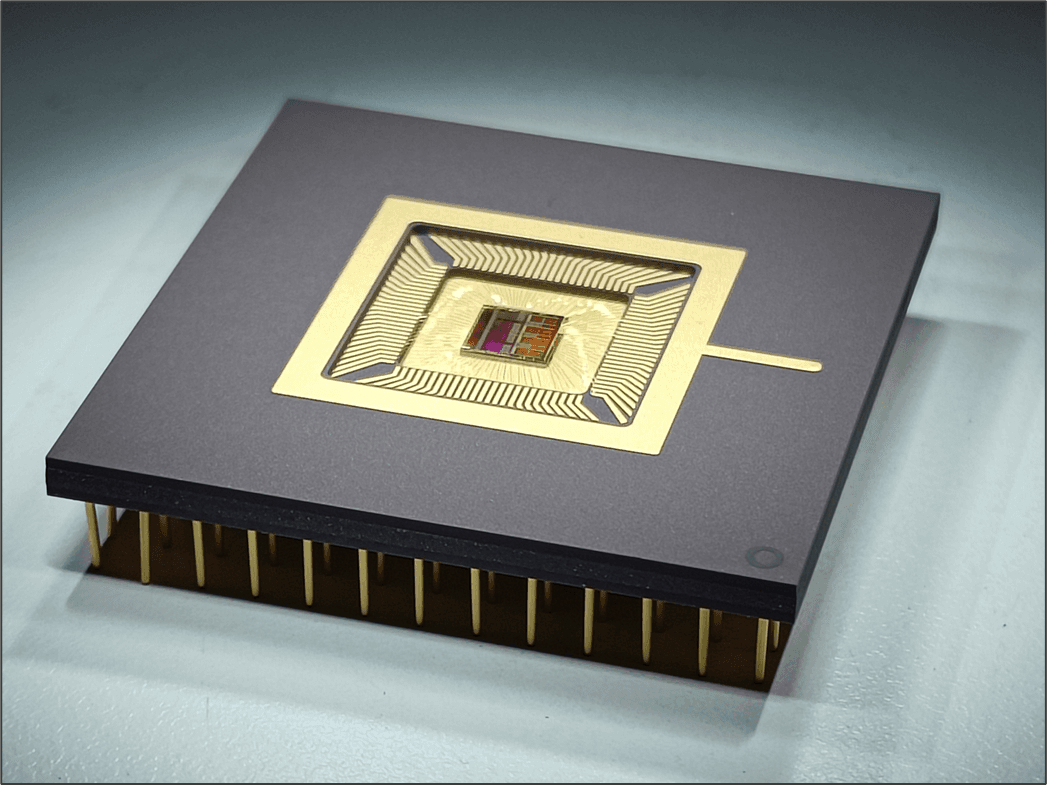

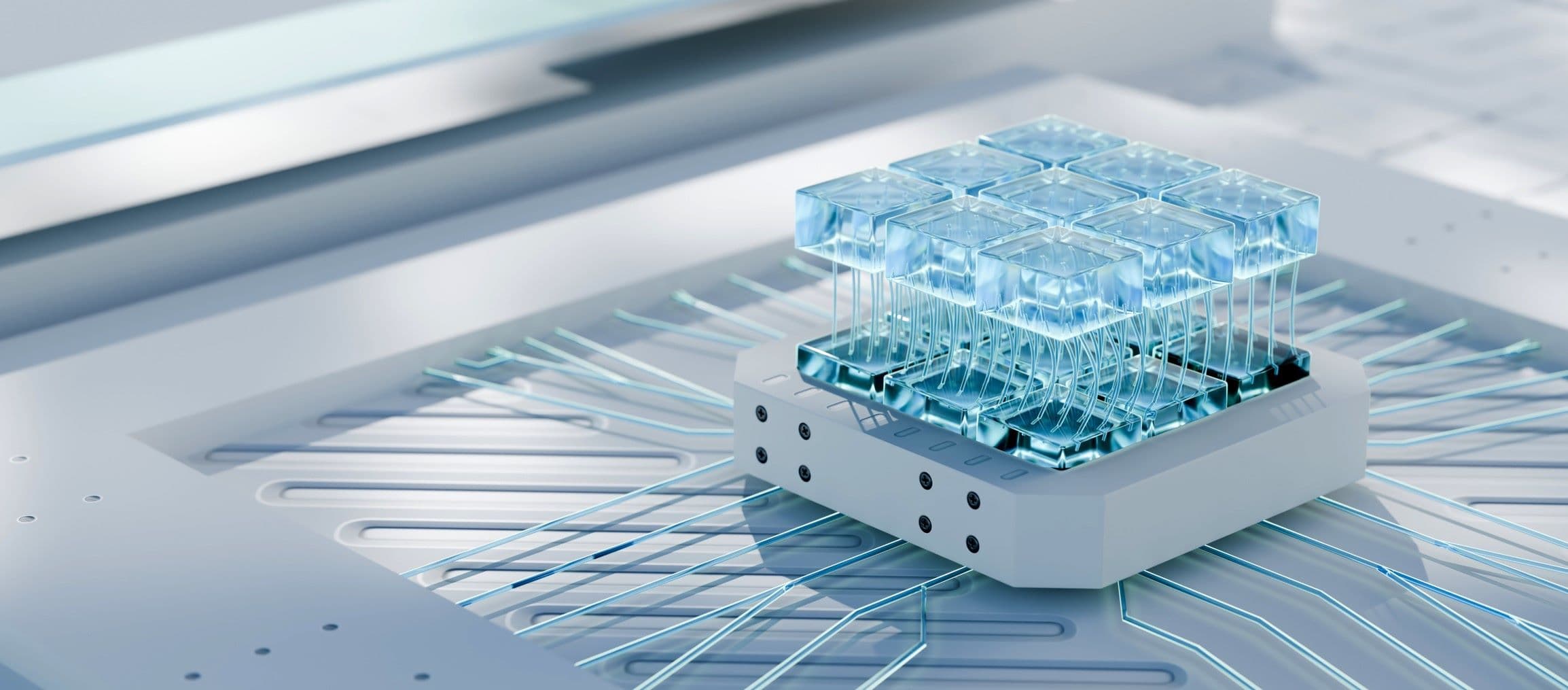

In his ambitions, Wieringa adheres to Moore's Law, which states that technological innovation in computer chips leads to the doubling of computing power every 12 months. The result: computers you can put in your pocket, which used to require entire halls. "If we realize a roadmap for international cooperation as we did in the chip industry, then you will have a usable implantable artificial kidney within fifteen years or so," Wieringa predicts. "The result won't be depending on the electronics, as imec is already proving. Partly thanks to ASML's EUV lithography, an incredible amount of electronics can be put on a square millimeter. And the Netherlands is also very strong in the field of Organs-on-a-chip, where living cells and chip technology work together. Combine those two strengths and you're at the global forefront."

Tradition

Sensational innovation regarding kidney health fits into a Dutch tradition. Indeed, the Dutch physician Willem Johan Kolff stood at the cradle of the very first hemodialysis machine and saved the first patient with acute kidney failure in Kampen on September 18, 1945. Since then, hemodialysis has saved millions of lives, but this mechanical blood purification system is by no means perfect. Moreover, the equipment essentially has changed very little in the last 50 years. Most people with kidney failure still have to visit a clinic several times a week for a treatment that is incredibly exhausting.

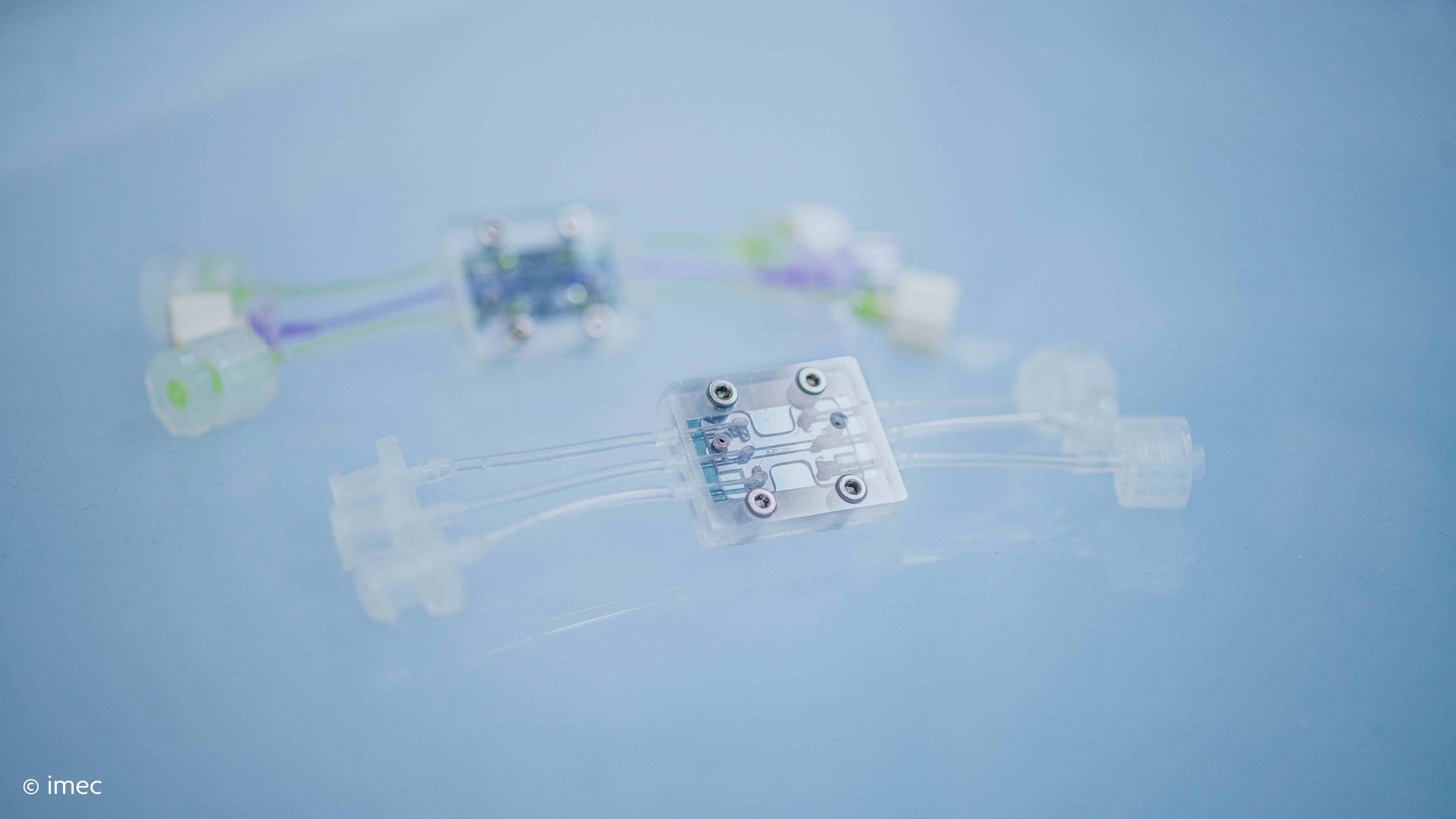

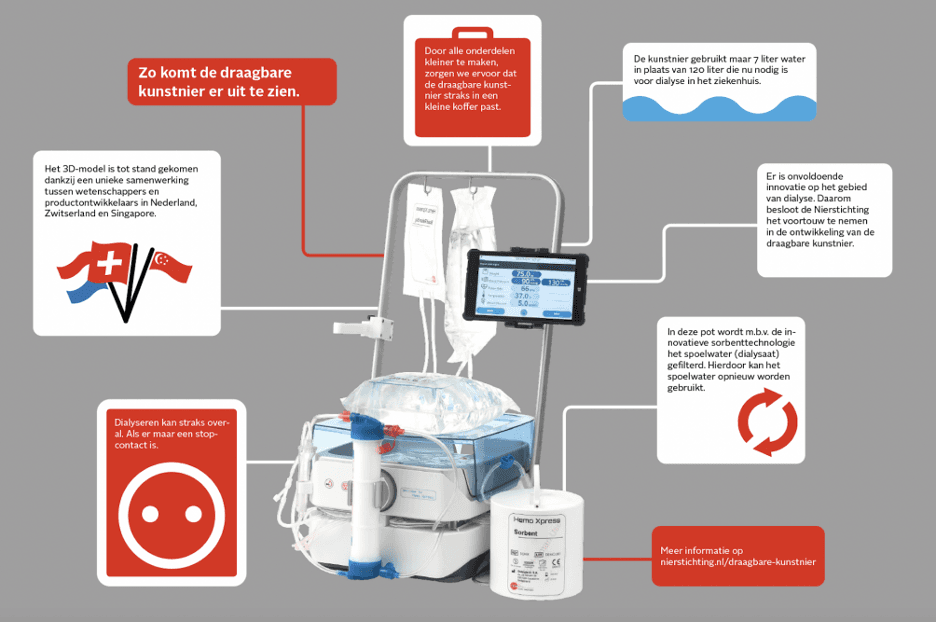

Meanwhile, the Kidney Foundation has been working for several years on a compact dialysis machine, so small that it can be taken on an airplane as hand luggage. This required several breakthroughs, but with the help of researchers from Holst Centre in Eindhoven, Debiotech from Lausanne, AWAK Technologies, Dialyss from Singapore, and a number of Dutch health insurers, developments have suddenly moved fast in the last 5 years, says Jasper Boomker of the Kidney Foundation.

The Dutch/Swiss company NextKidney was founded, which can show the first prototype later this year, according to Boomker. Together with the UMC Utrecht, these organizations are working hard to prepare for the clinical tests that will take place in 2022. The device is easy to connect to any ordinary power outlet (even ungrounded). Moreover, unlike classic dialysis equipment, it does not require 70 - 120 liters of water, but 6 liters is enough.

What does a kidney actually do?

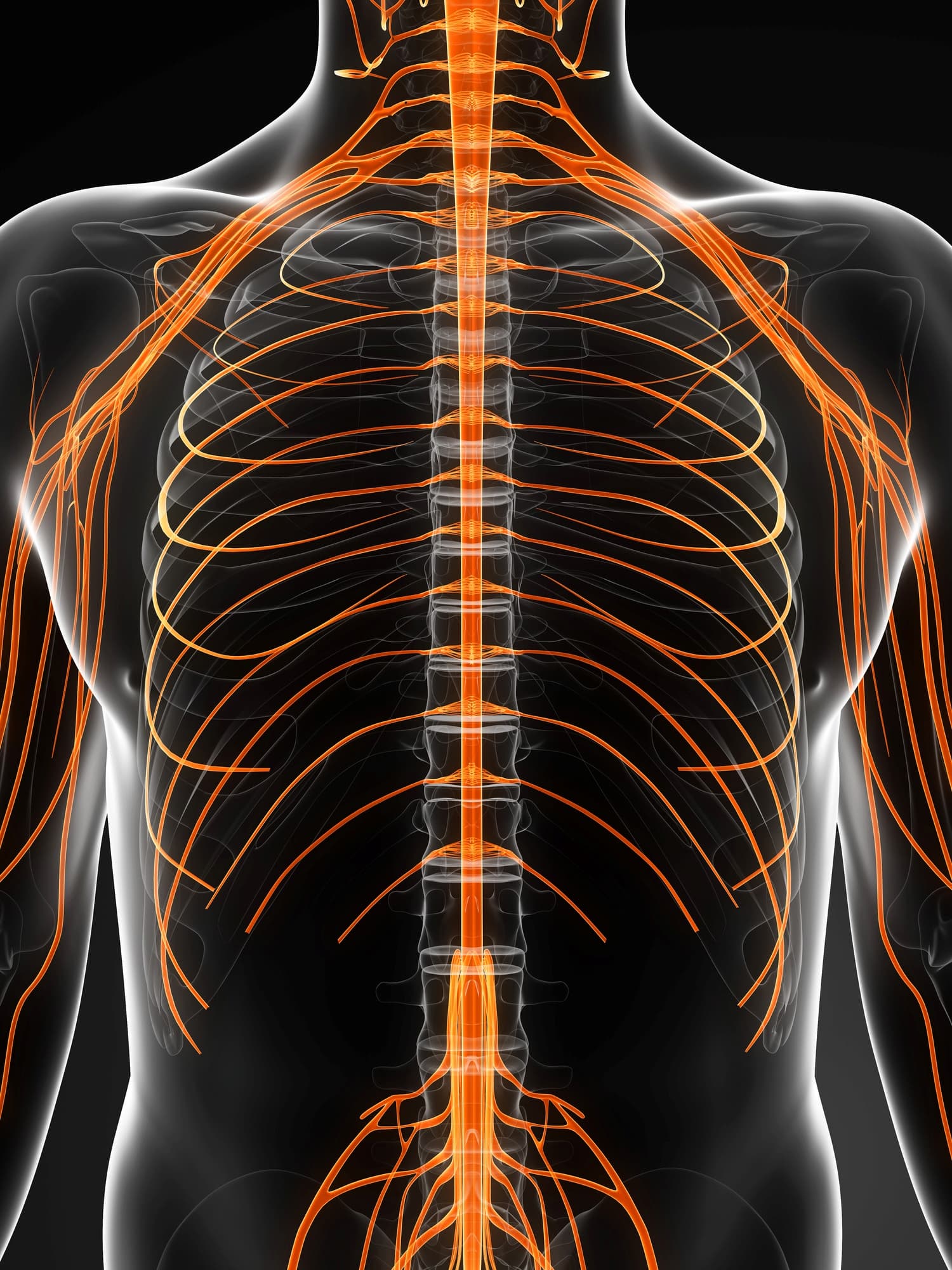

A dialysis device or artificial kidney partially takes over the function of a real kidney. But what do the kidneys do in the body?

Every person has two kidneys, each consisting of a complex grid of hundreds of thousands of tiny filters called nephrons. Those nephrons purify the blood and ensure its constant balance and quality.

The filtered out toxins, such as urea, leave the body through the urine, while useful substances that we still need are recycled by the kidney. These include vitamins, minerals, salts, water, and glucose.

In many kidney diseases, however, this purification works less and less well, which eventually - if the kidneys work for less than 15% - is fatal without dialysis or kidney transplant.

Transplant

Currently, according to Boomker, the best treatment for kidney failure is the transplantation of a donor’s kidney. "But unfortunately we all know that there is a great shortage of these," he says. So kidney patients remain mostly dependent on bulky and expensive blood dialysis machines that, despite their size, do not work nearly as efficiently as a real kidney.

One of the disadvantages of such a device is that in 3 treatments of 4 hours you try to "catch up" with the purification work that the kidneys do continuously 24 hours a day. That puts a particularly heavy burden on the heart, says Wieringa. "It's also not really environmentally friendly when you consider the amount of electricity and water required for current equipment."

Like Boomker, Wieringa has been involved in the project to drastically improve dialysis equipment for some time. Until 2017 this was from TNO in Delft and then from imec at Holst Centre, where they have the knowledge to use nanotechnology to make electrical devices ever smaller. NextKidney's portable artificial kidney could turn an entire industry on its head, Wieringa says. A "disruptive technology," in other words, similar to the electric car or the Internet. "This can improve and save the lives of many people, by also serve countries with poor infrastructure. And if we then push forward even further with an implantable artificial kidney, the social impact becomes greater again."

Less water

"One of the main goals was to develop an artificial kidney that requires less water," Boomker says. Dialyss, a spin-off company from the Singaporean Temasek Polytechnic, had a potential solution: sorbent technology. Temasek’s technology was already being used by the company AWAK for dialysis of fluid in the abdominal cavity. "This allowed us to go from over 100 liters to 6 liters," Boomker says.

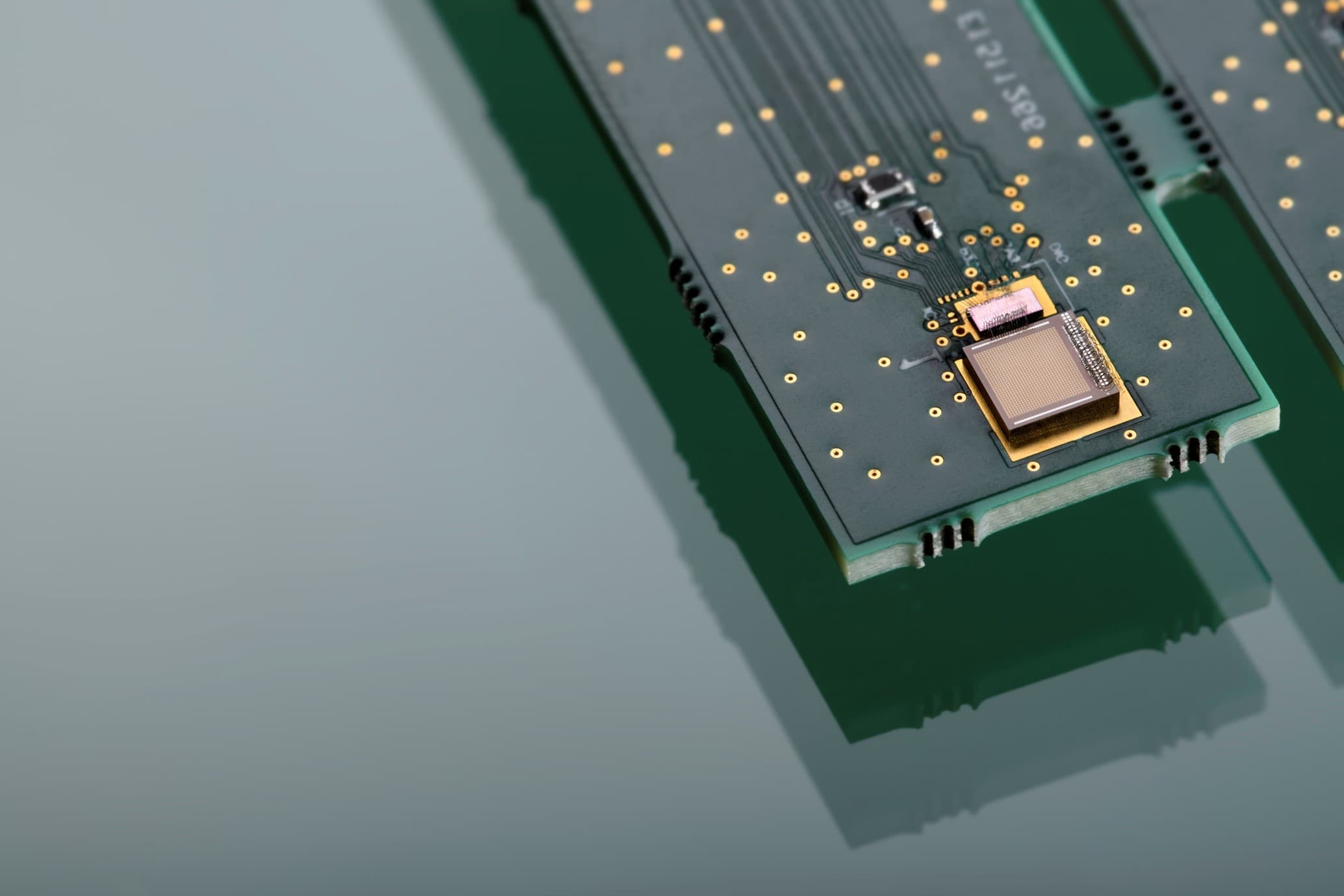

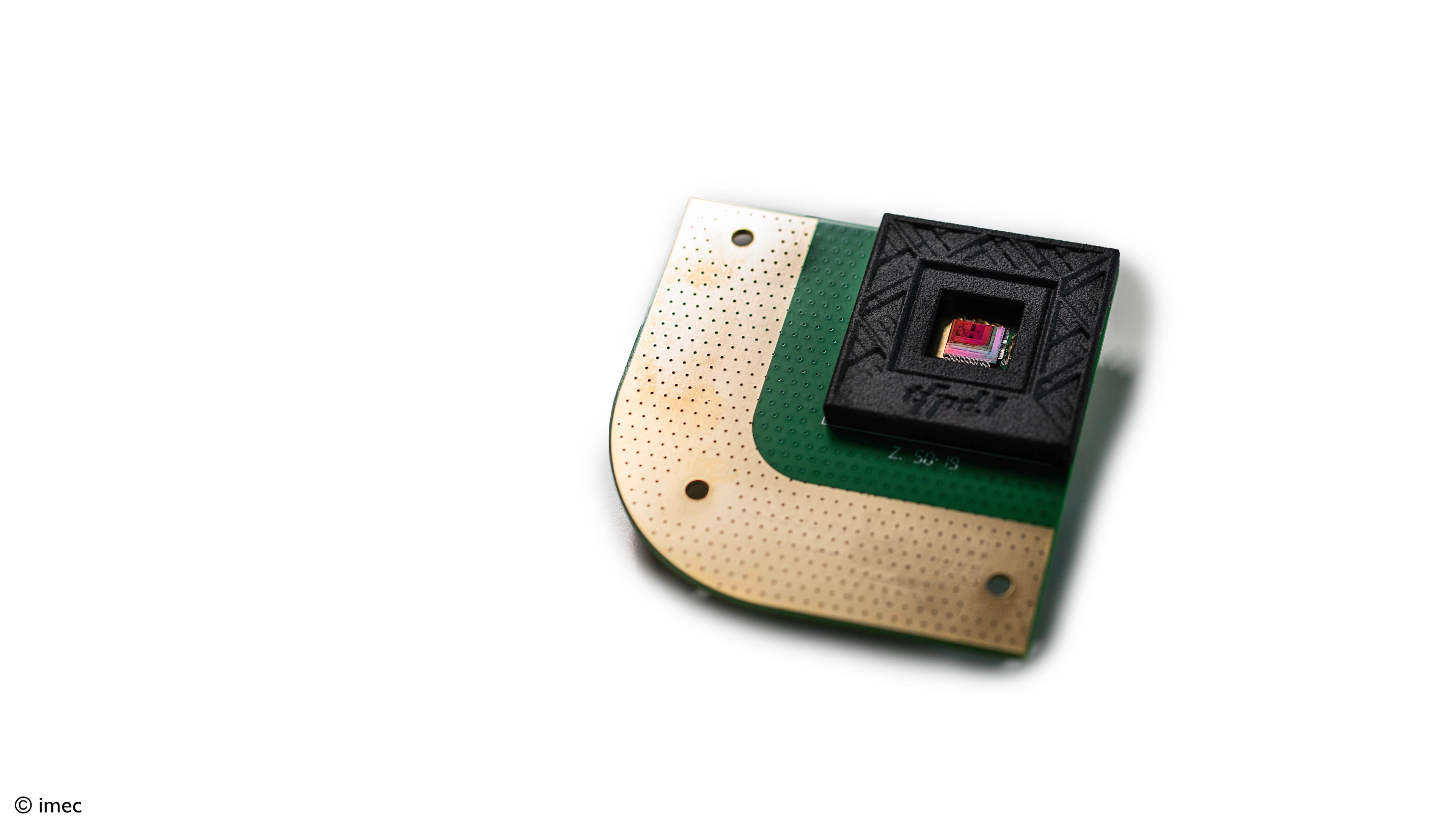

The Swiss company Debiotech, together with imec and others, then went to work on the design of the smaller artificial kidney. "A dialysis machine is full of sensors," explains Wieringa. "With our knowledge of nanotechnology, we are able to make those sensors and other electronics very small." The importance of those sensors can hardly be overstated, says Wieringa. Not only does the quality of the blood have to be measured, but the patients themselves also have to be continuously monitored when they are on dialysis at home at night, for example.

Wieringa gives the example of automatic needle alarms. "The worst form of blood leakage is when the return needle (which brings the purified blood back into the patient) detaches, while the machine continues to pump blood out of the patient via the other needle, which ultimately can lead to death. Within its activities at Holst Centre, imec has achieved international recognition within its activities at Holst Centre for sensor technology that immediately sets off an alarm and also stops the blood pump as soon as blood leaks."

And so, according to Wieringa, there are more sensors that can make home dialysis just as safe as in the hospital. In principle, it would even be possible to monitor a patient completely remotely and, in the event of questions, to provide assistance by telephone or video link (even via the device itself).

In this project, Wieringa is also very concerned with the regulations surrounding equipment and medical services. "You can't just develop a device and bring it to market. There are numerous standards that must be met. Committees have to look at the new technology and give their approval. It's important to consider this very early in the development process and, above all, to let the patients' voices be heard."

Vested interests

An inhibiting factor here - and this applies to more disruptive technologies - is that a lot of persuasion is needed to get the "old" dialysis equipment manufacturers and regulators on board. Wieringa: "Don't forget that this is an industry in which tens of billions of euros are involved, with high-profit margins, both for manufacturers of machines and clinics. Their support is crucial, however, because this is where the power lies to ultimately be able to make millions of portable artificial kidneys at the lowest possible price, with a global service." The innovators have to overcome a double hurdle, so to speak: the recognition that the existing equipment may eventually cease to be used, in addition to the business risk surrounding the development of a new device.

And that's not all, says director Tom Oostrom of the Dutch Kidney Foundation: "The reimbursement rates for current blood dialysis are under pressure worldwide, forcing the dialysis industry to adapt the current business model. What does help with this is the broad support for innovation in dialysis from the United States."

Technical hurdles for NextKidney's artificial kidney are few, according to Boomker. The main issues now are clinical trials and finding new investors. Like Wieringa and Oostrom, he is hopeful. "With this, the Netherlands can once again show the world how we can turn our technological expertise into usefulness for society."

Dutch version

Toekomstperspectieven voor nierpatiënten: via een dialyseapparaat in je rolkoffer naar een volledig implanteerbaar kunstorgaan

Een normaal leven is voor de meeste dialysepatiënten zo goed als onmogelijk. Naast de constante hinder en vermoeidheid, is er de noodzaak om meerdere keren per week urenlang in het ziekenhuis aan de dialyse te liggen. Maar er is licht aan het eind van de tunnel: de Nierstichting werkt momenteel samen met onderzoekers van o.a. imec in het Holst Centre aan de ontwikkeling van een draagbare kunstnier. Dit compacte dialyseapparaat - passend in een rolkoffer - zou het leven van nierpatiënten in de hele wereld al een stuk draaglijker kunnen maken. Maar het uiteindelijke doel van deze onderzoekers ligt nog een stap verder: de ontwikkeling van een implanteerbare kunstnier die de ingrijpende behandeling van nierdialyse op termijn helemaal overbodig zou kunnen maken.

Toekomstmuziek? Het is lastig om er een exacte termijn aan te hangen, maar de vorderingen tot nu toe laten zien dat het een realistische ambitie is, zegt Fokko Wieringa, bij imec verantwoordelijk voor het onderzoek naar de kunstnier. De compactere oplossing die de Nierstichting nog dit jaar wil presenteren is een eerste stap, zegt hij. “Maar ondertussen werken we voor de langere termijn ook al toe naar een nog kleiner apparaat; zo klein dat het uiteindelijk als kunstnier geïmplanteerd kan worden.” De rol van de elektrische bloedpomp - essentieel in een traditioneel dialyseapparaat - wordt dan overgenomen door het hart en de afvalstoffen verlaten het lichaam via de urine, net als bij een echte nier dus.

Wieringa houdt zich in zijn ambities vast aan de Wet van Moore die zegt dat technologische innovatie bij computerchips zo groot is dat de rekenkracht elke 12 maanden verdubbelt. Het gevolg: computers die je in je broekzak kunt steken, waar vroeger hele hallen voor nodig waren. “Als we net als in de chipindustrie een roadmap voor internationale samenwerking realiseren, dan heb je binnen een jaar of vijftien een bruikbare implanteerbare kunstnier”, voorspelt Wieringa. “Aan de elektronica zal het niet liggen, dat bewijst imec nu al. Mede dankzij ASML’s EUV-lithografie kan ongelofelijk veel elektronica op een vierkante millimeter gezet worden. En Nederland is ook erg sterk op het gebied van Organs-on-Chip, waarbij levende cellen en chiptechnologie samenwerken. Combineer die twee sterke punten en je staat wereldwijd voorop.”

Traditie

Opzienbarende vernieuwingen op niergebied passen in een Nederlandse traditie. De Nederlandse arts Willem Johan Kolff stond namelijk aan de wieg van het allereerste hemodialyseapparaat en redde op 18 September 1945 in Kampen de eerste patiënt met acuut nierfalen. Sindsdien heeft hemodialyse miljoenen levens gered, maar perfect is deze machinale bloedzuivering nog geenszins. De apparatuur is bovendien de laatste 50 jaar in diepste wezen nauwelijks veranderd. De meeste mensen met nierfalen moeten nog altijd meerdere malen per week naar een kliniek, voor een behandeling die dodelijk vermoeiend is.

Inmiddels werkt de Nierstichting al een aantal jaren aan een compact dialyseapparaat, zo klein dat het als handbagage in een vliegtuig meegenomen kan worden. Daarvoor waren meerdere doorbraken nodig, maar met hulp van onderzoekers van Holst Centre in Eindhoven, Debiotech uit Lausanne, AWAK Technologies en Dialyss uit Singapore en een aantal Nederlandse zorgverzekeraars gaan de ontwikkelingen de laatste 5 jaar opeens snel, vertelt Jasper Boomker van de Nierstichting.

Het Nederlands/Zwitserse bedrijf NextKidney werd opgericht, dat later dit jaar volgens Boomker het eerste prototype kan laten zien, en met het UMC Utrecht wordt hard gewerkt aan de voorbereidingen van klinische testen die in 2022 plaatsvinden. Het apparaat is makkelijk aan te sluiten op elk gewoon stopcontact (zelfs ongeaard). In tegenstelling tot klassieke dialyseapparatuur is er bovendien geen 70 - 120 liter water nodig, maar is 6 liter genoeg.

Wat doet een nier eigenlijk?

Een dialyseapparaat of kunstnier neemt deels de functie over van een echte nier. Maar wat doen de nieren in het lichaam?Ieder mens heeft twee nieren, elk bestaand uit een complex raster van honderdduizenden kleine filtertjes, nefronen genaamd. Die nefronen zuiveren het bloed en zorgen voor een constante balans en kwaliteit.

De uitgefilterde gifstoffen, zoals ureum, verlaten het lichaam via de urine, terwijl nuttige stoffen die we nog nodig hebben door de nier worden gerecycled. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan vitamines, mineralen, zouten, water en glucose.Bij veel nierziektes werkt die zuivering echter steeds minder goed, wat uiteindelijk – als de nieren voor minder dan 15% werken – dodelijk is zonder dialyse of niertransplantatie.

Transplantatie

© Nierstichting

Op dit moment is volgens Boomker de beste behandeling van nierfalen de transplantatie van een donornier. “Maar helaas weten we allemaal dat daar een groot tekort aan is.” Nierpatiënten blijven dus veelal aangewezen op omvangrijke en dure bloeddialyseapparaten die ondanks hun omvang lang niet zo efficiënt werken als een echte nier.

Een van de nadelen van zo’n apparaat is dat je in 3 behandelingen van 4 uur het zuiveringswerk probeert “in te halen” dat de nieren 24 uur per dag continu doen. Dat belast vooral het hart zwaar, zegt Wieringa. “Het is bovendien ook niet echt milieuvriendelijk als je kijkt naar de hoeveelheid stroom en water die voor de huidige apparatuur nodig zijn.”

Wieringa is net als Boomker al een tijd betrokken bij het project om de dialyseapparatuur drastisch te verbeteren. Tot 2017 was dat vanuit TNO in Delft en daarna vanuit imec bij Holst Centre, waar ze de kennis in huis hebben om met nanotechnologie elektrische apparaten steeds kleiner te maken. De draagbare kunstnier van NextKidney kan volgens Wieringa een hele industrie op zijn kop zetten. Een “disruptieve technologie” dus, vergelijkbaar met de elektrische auto of het internet. “Dit kan het leven van veel mensen verbeteren en redden, doordat ook landen met een gebrekkige infrastructuur bediend kunnen worden. En als we daarna nog verder doorzetten met een implanteerbare kunstnier wordt het maatschappelijk effect opnieuw groter.”

Minder water

“Een van de belangrijkste doelstellingen was om een kunstnier te ontwikkelen die minder water nodig heeft”, vertelt Boomker. Dialyss, een spin-off van het Singaporese Temasek Polytechnic, had een oplossing: sorbent technologie. AWAK gebruikte Temaseks technologie al voor de dialyse van vloeistof in de buikholte. “Hierdoor konden we van meer dan 100 liter naar 6 liter”, zegt Boomker.

Het Zwitserse Debiotech ging vervolgens, samen met o.a. imec, aan de slag met de vormgeving van de kleinere kunstnier. “Een dialyseapparaat zit vol sensoren”, legt Wieringa uit. “Met onze kennis van nanotechnologie zijn wij in staat die sensoren en andere elektronica heel klein te maken.” Het belang van die sensoren is groot, zegt Wieringa. Niet alleen de kwaliteit van het bloed moet gemeten worden, ook de patiënten zelf moeten continu in de gaten gehouden worden als ze bijvoorbeeld ’s nachts thuis de dialyse uitvoeren.

Wieringa geeft het voorbeeld van automatische naald-alarmering. “De ergste vorm van bloedlekkage is als de retournaald (die het gezuiverde bloed terug brengt in de patiënt) losschiet, terwijl de machine via de andere naald doorgaat met bloed uit de patiënt pompen, wat in het ergste geval kan leiden tot de dood. Imec heeft binnen haar activiteiten bij Holst Centre internationale erkenning bereikt voor sensortechnologie die direct een alarm af laat gaan en ook de bloedpomp stopt zodra er bloed lekt.”

En zo zijn er volgens Wieringa meer sensoren die thuisdialyse net zo veilig maken als in het ziekenhuis. In principe zou het zelfs mogelijk zijn een patiënt volledig op afstand te monitoren en bij vragen telefonisch of met videoverbinding (zelfs via het apparaat zelf) te helpen.

Wieringa houdt zich in dit project daarnaast veel bezig met de hele regelgeving rondom apparatuur en medische dienstverlening. “Je kunt niet zomaar een apparaat ontwikkelen en dan naar de markt brengen. Er zijn tal van normen waaraan voldaan moet worden. Commissies moeten zich buigen over de nieuwe technologie en hun goedkeuring verlenen. Het is belangrijk om daar al heel vroeg in het ontwikkelproces bij stil te staan en daarbij vooral ook de stem van de patiënten te laten horen.”

Gevestigde belangen

Een remmende factor daarbij is – en dat geldt voor meer disruptieve technologieën – dat er veel overtuigingskracht nodig is om de “oude” fabrikanten van dialyseapparatuur en de toezichthouders mee te krijgen. Wieringa: “Vergeet niet dat dit een industrie is waar tientallen miljarden euro’s in omgaan met hoge winstmarges, zowel bij producenten van machines als in klinieken. Hun steun is echter cruciaal, want hier zit de kracht om uiteindelijk miljoenen draagbare kunstnieren te kunnen maken tegen een zo laag mogelijke prijs, met een wereldwijde service.” Ze moeten als het ware een dubbele drempel overwinnen: de erkenning dat de bestaande apparatuur mogelijk op termijn niet meer gebruikt wordt en daarnaast het zakelijke risico rond de ontwikkeling van een nieuw apparaat.

En dat is niet het enige, zegt directeur Tom Oostrom van de Nierstichting: “De vergoedingen voor de huidige bloeddialyse staan wereldwijd onder druk, waardoor de dialyse-industrie genoodzaakt is het huidige businessmodel aan te passen. Wat daarbij wel helpt is de brede steun voor innovatie in dialyse vanuit de Verenigde Staten.”

Technische hordes voor NextKidney’s kunstnier zijn er volgens Boomker nauwelijks. Het gaat nu vooral om de klinische trials en het vinden van nieuwe investeerders. Net als Wieringa en Oostrom is hij hoopvol. “Hiermee kan Nederland de wereld opnieuw laten zien hoe we onze technologische expertise kunnen omzetten in nut voor de samenleving.”

Published on:

8 June 2021