In this series of Moonshot interviews, imec Netherlands talks to experts about the impact of nanotechnology on our future society. In this second episode, Dianda Veldman, director of the Netherlands Patients Federation, together with Patrick van Deursen, Program Director Health at imec within Holst Center, explores the role technology can play in making patients feel more human again.

The Netherlands ranks among the most prosperous countries in the world, with the highest life expectancy. The downside to this, is that stress and typical lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and obesity are relatively common. No less than 57% of the Dutch have one or more chronic conditions, among the over-75s this percentage even rises to 95. More and more Dutch people are therefore categorized as patients with one or more conditions, who depend on healthcare. Can technology help us to reduce the daily impact of that care need and allow people without patient stigma to fully participate in society again?

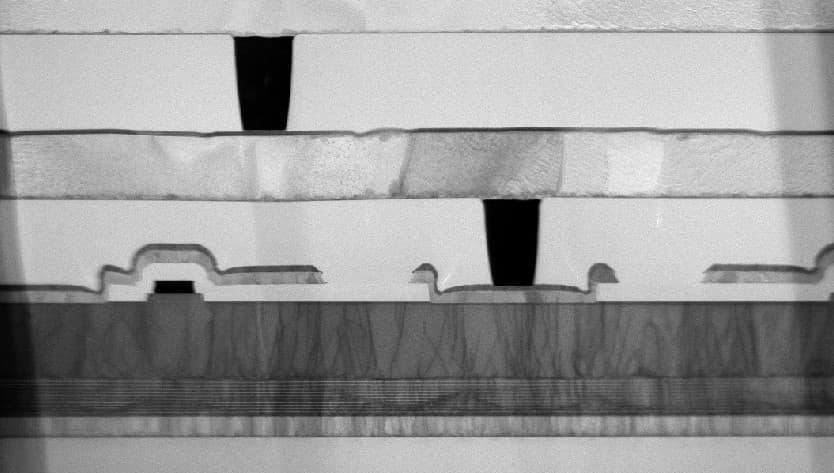

Patrick van Deursen is convinced that it’s possible. From imec, he and his team work within Holst Center on promising care applications based on microelectronics, to restore patients' quality of life. He gives an example: “When you have diabetes your daily life completely revolves around insulin injections. Furthermore, in case of kidney failure, it’s very common that you need to go to the hospital for kidney dialysis three times a week. At imec, we work together with, among others, the Kidney Foundation on the development of an artificial kidney. We proceed with small steps, and our first goal is to make the dialysis process more intelligent, and then portable. Ultimately, the artificial kidney could become an implantable device, that can actually technically replace your kidney.” Dianda Veldman is also a great proponent of technology in healthcare: “I think this is an excellent example of the vision that we have formulated for 2030 at the Patients Federation: ‘more human and less patient’.” Patrick: “Our one-liner from imec has a similar meaning: ‘taking the patient out of the person’.”

"Make yourself redundant as a specialist"

In daily practice, Dianda comes across many prejudices about technology in healthcare. “It would be at the expense of the warm personal attention. But I don't see it as a contradiction. In the book "Deep Medicine" Eric Topol describes how technology, and especially AI, can actually help us to spend more time with the patient. You need both. Real care can therefore also mean that you can avoid needing care.” Patrick agrees. “I think chronic care is one of the biggest challenges. For me the question is not: how can you improve chronic care, but how can you ensure that someone is no longer a chronic patient? In fact, your ultimate goal as a specialist should be to make yourself redundant. With primary prevention, such as lifestyle changes, you can partially achieve that goal, but you also have to take external factors and DNA into account. Then the next step is secondary prevention, to ensure that people stay out of that chronic care system.” Dianda: “Exactly, support people who are at risk so the risk will not erupt.”

“The hospital should be able to repair you”

How does Dianda see the vision ‘more human, less patient’ become a reality in the future? “In the first place, it means that we have to work towards a situation in which it is easier for everyone to stay healthy. Technology can certainly play a role in this, but it also requires human behavior, plus a living environment that stimulates healthy choices. And when you do get ill, you should have more control over your situation. That is why we argue, partly as a result of the corona crisis, for hybrid care. During this lockdown, we already see digital solutions for remote care next to phone services. We want to continue to work with this after this crisis. With remote guidance the urgency to go to the hospital is a lot less.” And if it turns out to be necessary to go to the hospital after all, treatments can improve considerably thanks to technology, she says. “By using surgical robots your hospital stay can be shortened significantly. And thanks to less invasive treatments, you recover faster. At the same time the role of doctors is changing. On the one hand, you will have generalists with a very broad spectrum of care who will coach you and point out the right care. On the other hand, you get highly specialized doctors who have all the accumulated global knowledge in this specific field and know how to use specialist instruments.” Patrick also sees the changing role of hospitals: “In future you should only need to go there when things really go wrong. You get your treatment and you leave hospital in a better state than when you went in. The current situation is like this: I suffer from kidney failure, I go to the hospital and I end up spending the rest of my life on dialysis. What you really want is to be ‘repaired’, no longer in need of care.”

Tailor-made medication

Nanotechnology has the potential, according to imec, to not only restore functions, but also to enlarge or transform human capabilities. Patrick: “With so-called wearables, ingestables and implantables, you will soon benefit from invisible, imperceptible technology on and inside your body that improves your health in a very precise and personal way. You are no longer aware of your condition.” Dianda: “Like a pacemaker.” Patrick: “I think that's a nice comparison. Despite the fact that you have a significant health issue, you are no longer constantly aware of it and you fully participate in society.” Dianda: “I truly feel sorry for all those women who suffered from breast cancer and depend on hormone therapy for years, which completely destroys their lives. This kind of treatment should be much more tailor-made.” Patrick: “That's right, a lot of people struggle with an enormous amount of pills every day. What if we could store medication in our bodies, which is then carefully distributed in exactly the right amount, at the right time?” Dianda: “That ties in nicely with the ‘more human, less patient’ pursuit: medication is no longer a hassle. And you are not worried about it either.”

“With so-called wearables, ingestables and implantables, you will soon benefit from invisible, imperceptible technology on and inside your body that improves your health in a very precise and personal way” - Patrick van Deursen

Diagnosis colon cancer

Unfortunately Dianda is an expert by experience. She was diagnosed with colon cancer in December last year. “I am clean after two operations, but for the next few years I will have to go to hospital every three months. I would really like it if there was some sort of device in my body that signals when something is wrong, that gives peace of mind. During that period I also spent a lot of time looking for data from patients like me with colon cancer. What is my survival rate? That’s why I absolutely believe in sharing global knowledge of medical doctors and patient data and make it accessible to everyone, so that you can diagnose more accurately and receive tailor-made treatments.”

Dianda touches on a sensitive issue: the sharing of data and privacy in healthcare. Patrick: “For me that is a technical-operational challenge, for which there are good technical solutions. AI-based technology makes it possible to securely exchange anonymized data. Dianda: “I am not an ICT specialist, but I am in favor of a data train that only collects relevant data. Patrick: “That's what we do with ‘privacy preserving’: only exchange data at the level of algorithms or warnings. Then you no longer have to send all raw data to the cloud. Moreover: when in future a device is placed on or inside your body, you can keep data completely to yourself. Only when an intervention is necessary does a signal go out.” Dianda: “I think we both feel that big data has a lot of advantages, but that at the same time you have to arrange privacy properly. For me that is also about political choices. When tech giants enter the healthcare market, there might be different interests at play. A doctor must take the Hippocratic Oath, but what about the Facebooks and Googles of this world? That ethical, governance side of healthtech is a very important one.”

“What is my survival rate? That’s why I absolutely believe in sharing global knowledge of medical doctors and patient data and make it accessible to everyone” - Dianda Veldman

Whats’ next?

Finally, if we look a little closer into our crystal ball: where will technology take us when we have overcome chronic diseases and added more and more healthy years to our lives? Patrick: “If we take it one step further we’re looking at augmentation of human. Then we’ll not only be able to repair what’s broken, but to actually improve a person.” Dianda: “As in human 2.0. Just like Yuval Noah Harari describes in his book ‘Homo Deus’, about makeable humans, who may one day become immortal. I think we should be careful with these kind of developments, which can also further widen the wealth gap.” Patrick: “We are already seeing it on a limited scale; humans are already better than 10,000 years ago. Are we going further in that direction? I don’t know. We will see.”

* Figures as of January 1, 2019 from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport published on Volksgezondheidenzorg.info

Dutch version

Kan technologie de zorg menselijker maken?

In deze serie Moonshot-interviews gaat imec Nederland in gesprek met experts over de impact van nanotechnologie op onze toekomstige samenleving. In deze tweede aflevering verkent Dianda Veldman, directeur van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, samen met Patrick van Deursen, Program Director Health bij imec binnen Holst Centre, welke rol technologie kan spelen om patiënten weer meer mens te laten zijn.

Nederland is een van de meest welvarende landen ter wereld, met een van de hoogste levensverwachtingen. De keerzijde is dat stress en typische welvaartziektes zoals diabetes en obesitas, relatief veel voorkomen. Maar liefst 57% van de Nederlanders heeft één of meer chronische aandoeningen, onder 75-plussers is dat zelfs 95%. Steeds meer Nederlanders zijn dus om een of meerdere redenen patiënt en afhankelijk van zorg. Kan technologie ons helpen om de dagelijkse impact van die zorgbehoefte kleiner te maken en mensen zonder patiëntstigma weer volledig laten deelnemen aan de samenleving?

‘Meer mens, minder patiënt’

Patrick van Deursen is ervan overtuigd dat het kan. Vanuit imec werkt hij binnen Holst Centre samen met zijn team aan veelbelovende zorgtoepassingen gebaseerd op micro-elektronica, die patiënten weer hun kwaliteit van leven teruggeeft. Hij geeft een voorbeeld: “Met diabetes ben je de hele dag bezig met prikken. Bij nierfalen moet je soms drie dagen per week naar het ziekenhuis voor nierdialyse. Bij imec werken we samen met onder andere de Nierstichting aan de ontwikkeling van een kunstnier. Dat gaat in kleine stappen, waarbij ons eerste doel is om het dialyseproces intelligenter te maken, en vervolgens draagbaar.

Uiteindelijk zal de kunstnier ook implanteerbaar worden, waardoor deze feitelijk jouw nier volledig technisch vervangt.”

Dianda Veldman is zelf ook een groot voorstander van technologie in de zorg: “Ik vind dit een mooi voorbeeld. Het sluit volledig aan bij de visie die we vanuit Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor 2030 hebben geformuleerd: ‘meer mens en minder patiënt’.” Patrick: “Onze oneliner vanuit imec heeft een vergelijkbare strekking: ‘taking the patient out of the person’.”

‘Maak jezelf als specialist overbodig’

In de dagelijkse praktijk komt Dianda veel vooroordelen tegen over technologie in de zorg. “Het zou ten koste gaan van de warme persoonlijke aandacht. Maar ik zie het niet als een tegenstelling. In het boek ‘Deep Medicine’ beschrijft Eric Topol hoe technologie, en met name AI, ons juist kan helpen om meer tijd te besteden aan de patiënt. Je hebt allebei nodig. Echte zorg kan dus ook zijn dat je kan voorkomen dat je zorg nodig hebt.”

Patrick is het daar mee eens. “Een van de grootste uitdagingen vind ik de chronische zorg. Voor mij is niet de vraag: hoe kun je die zorg verbeteren, maar hoe kun je er voor zorgen dat iemand geen chronisch patiënt meer is? Eigenlijk zou je doel als specialist moeten zijn om jezelf overbodig te maken. Met primaire preventie, zoals verandering van levensstijl, kun je dat wel deels bereiken, maar je hebt ook nog externe factoren en DNA. Dan kom je uit bij secundaire preventie, oftewel: hoe kun je zorgen dat mensen uit dat chronische systeem blijven.”

Dianda: “Precies, mensen die een risico lopen, ondersteunen zodat het risico niet tot uitbarsting komt.”

‘Ziekenhuis moet je repareren’

Hoe ziet Dianda de visie ‘meer mens, minder patiënt’ in de toekomst werkelijkheid worden? “In de eerste plaats betekent dat werken aan een situatie waarin het voor iedereen makkelijker is om gezond te blijven. Daar kan technologie zeker een rol in spelen, maar daar is ook menselijk gedrag voor nodig, plus een leefomgeving die gezonde keuzes stimuleert. Als je ziek bent, moet je daar vervolgens meer eigen regie op krijgen. Daarom pleiten wij, en dat is deels voortgekomen uit de coronacrisis, voor hybride zorg. Tijdens de lockdown zie je naast de telefoon al digitale oplossingen voor zorg op afstand. Wij willen daar ook na deze crisis mee blijven werken. Met telebegeleiding hoef ik niet meer voor alles naar het ziekenhuis.” Als dat toch nodig blijkt, kunnen behandelingen volgens haar dankzij technologie flink verbeteren. “Met gebruik van operatierobots hoef je minder lang in het ziekenhuis te blijven. En dankzij minder invasieve behandelingen herstel je sneller. De rol van artsen verandert. Enerzijds zal je hele brede generalisten hebben, die jou coachen en wijzen op de juiste zorg. Anderzijds krijg je zeer gespecialiseerde artsen die alle verzamelde wereldwijde kennis op dit specifieke vlak hebben en weten hoe ze specialistische instrumenten moeten inzetten.” Ook Patrick ziet de rol van ziekenhuizen veranderen: “Daar moet je alleen nog maar komen als het echt mis is. Je krijgt er een behandeling en je komt er beter uit dan toen je er in ging. Nu is het bijvoorbeeld zo: ik heb last van nierfalen, ik ga naar het ziekenhuis en ik zit de rest van mijn leven aan de dialyse. Terwijl je gerepareerd wilt worden, van zorgbehoevend naar geen zorg.”

Medicatie op maat

Nanotechnologie heeft volgens imec de potentie om niet alleen functies te herstellen, maar ook menselijke vermogens te vergroten of te transformeren. Patrick: “Met zogeheten wearables, ingestables en implantables profiteer je straks van onzichtbare, onmerkbare technologie op en in je lichaam die op een heel precieze, persoonlijke manier je gezondheid verbetert. Je bent je er niet meer bewust van dat je een aandoening hebt.”

Dianda: “Zoals bij een pacemaker.” Patrick: “Dat vind ik een mooie vergelijking. Feitelijk heb je een heel groot probleem, maar je bent daar niet meer dagelijks mee bezig en je draait volledig mee in de maatschappij.” Dianda: “Wat ik zo erg vind is al die vrouwen met borstkanker, die jarenlang hormonen slikken waardoor ze geen leven meer hebben. Zo’n behandeling zou veel meer op maat moeten kunnen.” Patrick: “Klopt, heel veel mensen worstelen dagelijks met een enorme hoeveelheid pillen. Kunnen we niet medicatie in het lichaam hebben, waarbij precies op maat de juiste hoeveelheid op exact het juiste moment wordt toegediend?” Dianda: “Dat sluit mooi aan bij dat meer mens, minder patiënt, je hebt er gewoon minder last van. En je bent er ook niet ongerust over.”

‘Met wearables, ingestables en implantables profiteer je straks van onzichtbare, onmerkbare technologie in je lichaam die op een heel precieze, persoonlijke manier je gezondheid verbetert’ - Patrick van Deursen

Diagnose darmkanker

Dianda is helaas ervaringsdeskundige. In december vorig jaar kreeg ze de diagnose darmkanker. “Na twee operaties ben ik schoon, maar de komende jaren moet ik elke drie maanden naar het ziekenhuis. Ik zou het heel fijn vinden als in mijn lijf iets zat dat signaleert als er iets aan de hand is, dat geeft rust. Ook heb ik in die periode enorm zitten zoeken naar data van vergelijkbare patiënten met darmkanker. Wat is mijn overlevingskans? Ik geloof daarom absoluut in het ‘patients like me’ argument om wereldwijde kennis van medici en patiëntendata te delen en toegankelijk te maken voor iedereen, zodat je nauwkeuriger een diagnose kunt stellen en behandelingen op maat krijgt.”

Dianda raakt aan een gevoelig punt, namelijk het delen van data en privacy in de zorg. Patrick: “Voor mij is dat een technisch-operationele uitdaging, met inmiddels goede technische oplossingen. Met op AI gebaseerde technologie is het mogelijk om veilig geanonimiseerde data uit te wisselen. Dianda: “Ik ben geen ICT-specialist, maar ik ben voorstander van een datatrein die alleen alle relevante data komt ophalen. Patrick: “Dat is wat we met privacy preserving doen: alleen op het niveau van algoritmes of waarschuwingen data uitwisselen. Dan hoef je niet meer alle ruwe data naar de cloud te sturen. Bovendien: als een device straks op of in je lichaam zit, kun je data helemaal bij jezelf houden. Alleen als er een ingreep nodig is, gaat er een signaal naar buiten.” Dianda: “We vinden denk ik allebei dat big data erg veel voordelen heeft, maar tegelijkertijd dat je die privacy goed moet regelen.

Voor mij gaat dat ook over politieke keuzes. Als grote techreuzen die zorgmarkt betreden, spelen er andere belangen. Een arts moet de Eed van Hippocrates afleggen, de Facebooks en Googles van deze wereld niet. Die ethische, governance kant is wel een heel belangrijke.”

‘Wat is mijn overlevingskans? Ik geloof daarom absoluut in het ‘patients like me’ argument om wereldwijde kennis van medici en patiëntendata te delen en toegankelijk te maken’ - Dianda Veldman

Whats’ next?

Tot slot, als we nog wat verder in de glazen bol kijken: we hebben de chronische ziektes overwonnen, we kunnen steeds meer gezonde jaren toevoegen aan ons leven, waar brengt de technologie ons dan? Patrick: ”Een stap verder is augmentation of human, dus hoe kan ik niet alleen repareren wat kapot is, maar hoe kan ik als mens verbeteren?”

Dianda: “De mens 2.0. Feitelijk zoals Yuval Noah Harari beschrijft in zijn boek ‘Homo Deus’, over de maakbare mens, die misschien wel ooit onsterfelijk wordt. Ik vind dat we voorzichtig moeten zijn met dit soort ontwikkelingen, die bovendien de welvaartskloof verder kan vergroten.”

Patrick: “We zien het op beperkte schaal nu al, we zijn als mens al beter dan 10.000 jaar geleden. Gaan we verder in die richting? Ik weet het niet. We gaan het zien.”

* Cijfers per 1 januari 2019 van het Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport gepubliceerd op Volksgezondheidenzorg.info

Over Dianda Veldman

Dianda Veldman is sinds 2015 directeur/bestuurder van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland. Ze studeerde Sociologie aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen en heeft een post master in bedrijfskunde en marketing. Dianda heeft meer dan dertig jaar ervaring in management- en directiefuncties, in het bedrijfsleven (o.a. KPN Telecom, Ogilvy & Mather en WPG Uitgevers) en de not-for-profit sector (Vereniging Eigen Huis, Stichting Rutgers).

Over Patrick van Deursen

Patrick van Deursen is Program Director Health en Department Director Solutions bij imec binnen Holst Centre. Met zijn team richt hij zich op de ontwikkeling en het naar de markt brengen van medische technologieën voor wearables, ingestables en implantables. Hiervoor was hij onder meer business development director bij Philips voor de Home Healthcare-portfolio in Europa, met de nadruk op e-Health-introducties. Patrick behaalde zijn diploma Werktuigbouwkunde aan de Universiteit van Delft en een MBA aan de Rotterdam School of Management.

Dianda Veldman has been director of the Netherlands Patient Federation since 2015. She studied Sociology at the University of Groningen and has a post master's degree in business administration and marketing. Dianda has more than thirty years of experience in management and board positions, in business (including KPN Telecom, Ogilvy & Mather and WPG Publishers) and the not-for-profit sector (Vereniging Eigen Huis, Rutgers Foundation).

Patrick van Deursen is Program Director Health and Department Director Solutions at imec within Holst Center. With his team, he focuses on the development and marketing of medical technologies for wearables, ingestables and implantables. Previously, he was business development director at Philips for the Home Healthcare portfolio in Europe, with an emphasis on e-Health launches. Patrick obtained his Mechanical Engineering degree from the University of Delft and an MBA from the Rotterdam School of Management.

Published on:

23 June 2021